Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe "Jelly Roll" (Mouton) Morton (October 20, 1890 - July 10, 1941) | |||

Selected Compositions - Earliest Confirmed Year Selected Compositions - Earliest Confirmed Year | |||

|

1915

[Original] Jelly Roll Blues [Chicago Blues]Superior Rag 1918

Frog-I-More Rag [Froggie Moore][Sweetheart o' Mine] 1923

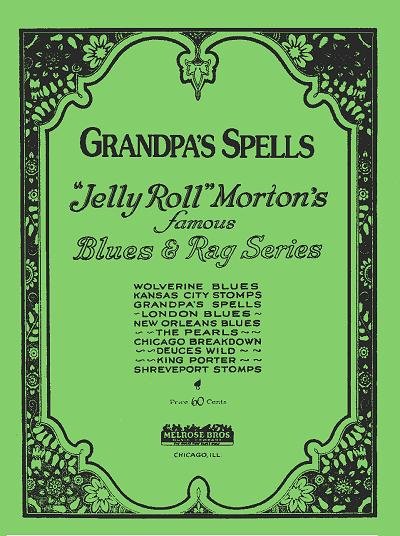

Grandpa's SpellsWolverine Blues [The Wolverines] [1] Kansas City Stomp[s] The Pearls Mr. Jelly Lord Big Foot Ham [Big Fat Ham] [Ham and Eggs] Muddy Water Blues[?] Mamanita King Porter Stomp Shreveport Stomp Chicago Breakdown [Stratford Hunch] New Orleans Blues [New Orleans Joys] [Low Down Blues] [Monrovia] London [Cafe] Blues [Shoe Shiner's Drag] (My Home Is In a) Southern Town Deuces Wild Any Ox 1924

Bucktown BluesMidnight Mama [Tom Cat Blues] 1925

Milenberg Joys [2,3]Black Bottom Stomp [Queen of Spades] 1926

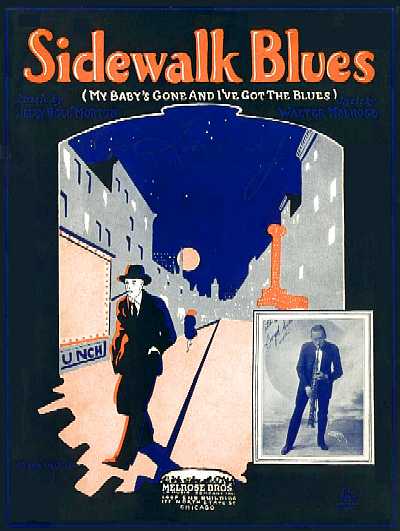

Sidewalk Blues [Fish Tail Blues]The Chant Fat Meat and Greens Dead Man Blues [4] Cannon Ball Blues [5,6] Stash that Cash [7] State and Madison: A Busy Stomp [7] Windy City Blues [7,8] 1927

Jungle BluesWild Man Blues [Ted Lewis Blues] Hyena Stomp Billy Goat Stomp 1928

Buffalo Blues [Mister Joe]boo [Gold Fish Blues] Low Gravy Honey Babe Georgia Swing Red Hot Pepper Sweet Anita Mine Deep Creek 1929

Seattle HunchPep Frances [Fat Francis] Freakish Tank Town Bump Down My Way Burnin' the Iceberg Pretty Lil New Orleans Bump Try Me Out Turtle Twist Smilin' the Blues Away Mississippi Mildred Courthouse Bump Sweet Peter Little Lawrence Mint Julep I Hate a Man Like You Don't Tell Me Nothin' 'Bout My Man My Little Dixie Home That's Like it Ought to Be 1930

Mushmouth ShuffleFussy Mabel Each Day If Someone Would Only Love Me That'll Never Do Croc-A-Dile Cradle Pontchartrain [Blues] [as Ponchatrain - sic] I'm Looking for a Little Bluebird Oil Well Primrose Stomp Harmony Blues Load of Coal Crazy Chords Strokin' Away Blue Blood Blues 1931

Dixie Knows [9]Fickle Fay Creep [Soap Suds] 1932

Gambling JackOa We E |

1933

Jersey [Jersey Joe]1938/c.1938 - LoC

The Finger Breaker [Finger Buster]Sweet Substitute If You Knew How I Love You The Perfect Rag [Sporting House Rag] Indian Song Moi Pas Taimez Ga Georgia Skin Spanish Swat Organ Interlude The Naked Dance [10] Mamie's Blues [219 Blues] [11] Why? [11] 1939

Don't You Leave Me Here [I'm AlabamaBound] The Crave Albert Carroll's Blues Good Old New York [World's Fair Song] [12] We Are Elks [12] We Will Never Say Goodbye [13] Winin' Boy Blues [Winding Boy] Anamule Dance [Animule] Michigan Water Blues 1940

Big Lip BluesDirty, Dirty, Dirty Get the Bucket Shake It Swinging the Elks Unpublished or Uncertain

Aaron Harris (Was a Bad, Bad Man)Alabama Nights Benny Frenchy's Defeat Bert Williams [The Pacific Rag] Betty Buddy Bertrand's Blues Buddy Bolden's Blues Buddy Carter Rag Cadillac Rag [?] C'etait N'autf' Can Can Card Dealer's Song [?] Crazy Chord Rag [Boogie Woogie Blues] Creepy Feeling Dear Ole Lonnon Discordant Jazz Exit Gloom Fast Ragtime Game Kid Blues Gan Jam Golden Wedding [Shreveport Stomp Waltz] Hen House High Brown Baby Mine [14] Hog Function Honky Tonk Music [Blues] Il Trovatore (The Miserere combined w/the Anvil Chorus) Jazz Jubilee Jelly Roll Morton's Scat Song La Paloma into Blues Levee Man Blues [Levee Rambler Blues] Melody with Break Melody with Riff My Darling is the Only One for Me New York Town One Straight Melody Prologue Opening Sammy Davis' Ragtime Style A Slow Jazz Tune Smart Set Stomp Stop & Go Stratford Rag [same as Hunch?] Sugary Superior Rag Sweet Jazz Music There's a Sign on Her Window Tom Cat Stomp Try and Get It Twenty Four Hours of Love Every Day ZZ

1. w/Benjamin Spikes & John Spikes

2. w/Paul Mares & Leon Roppolo 3. w/Walter Melrose 4. w/Anita Gonzalez 5. w/Charlie Rider 6. w/Marty Bloom 7. w/Bob Peary & Charles Raymond 8. w/Jimmie Hudson 9. w/Mel Stitzel 10. from Tony Jackson 11. from Mamie Desdunes 12. w/Ed Werac 13. w/Paul Watts 14. w/Karl Kramer | ||

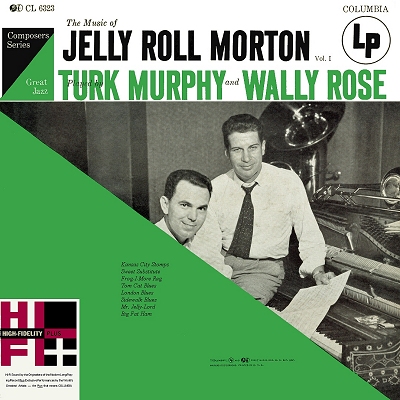

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |||

| |||

Known Rollography Known Rollography | |||

| |||

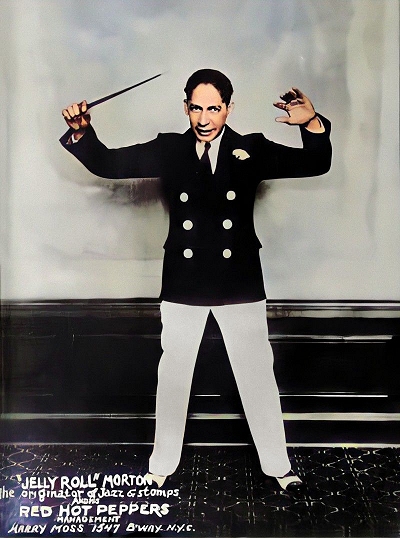

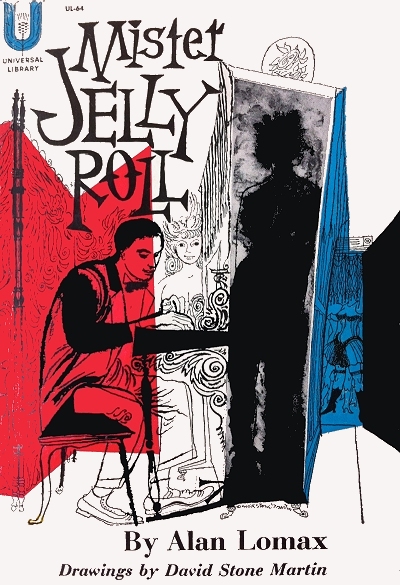

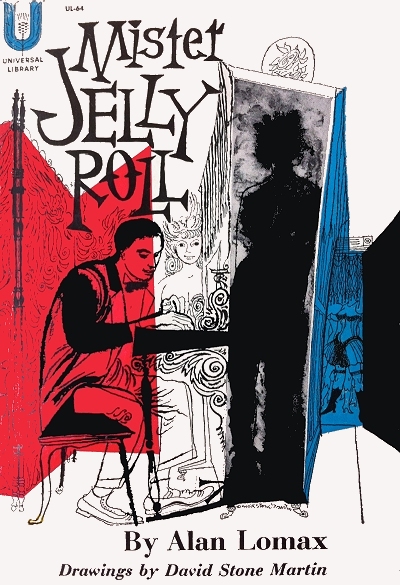

There are some musicians who come along and make waves either through their antics, their bravado, or their performance skills. Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton was one of those individuals who managed to captivate fans and raise the eyebrows (and the ire) of other musicians through all three. In this instance, also, it is hard to peg him into a single genre, other than "Jelly Roll Style," given how different and distinctive both his performance and writing of rags and blues was. He left behind one of the more important looks at the origins of ragtime, at least in New Orleans and the South, through a series of remarkable conversations recorded in 1938 and 1939. However, it was his own music and unique style that propelled him to fame, pushed him into obscurity, then resurrected while ostensibly killing him at the same time. Although the most traditional source for his story was long held to be the widely regarded 1950 book by Alan Lomax, Mister Jelly Roll, research of the 21st century by the author and a number of his distinguished peers has turned up a much more accurate look at Morton's variegated story, of which a condensed version is presented here.

Early Life in New Orleans

The self-proclaimed inventor of Jazz and Stomp music, "Jelly Roll" Morton grew up in the right environment to absorb a variety of musical influences: New Orleans, Louisiana. He was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, out of legal wedlock (in a common law marriage) to Edward Joseph Lamothe (or Lemott) and Louise Hermance Monette (or Monett). The often-cited date of September 20 does not align with the official baptismal registry in New Orleans, which insists on an October 20 birth, so the latter will be accepted for this essay as the potentially most accurate accounting, even though Morton himself continued to write September 20 throughout his life. When he was around three or so, Louise left her situation with Lamothe and was soon married to William Mouton on February 5, 1894. Ferd would eventually adopt a variation of his stepfather's last name as his own, morphed into Morton.

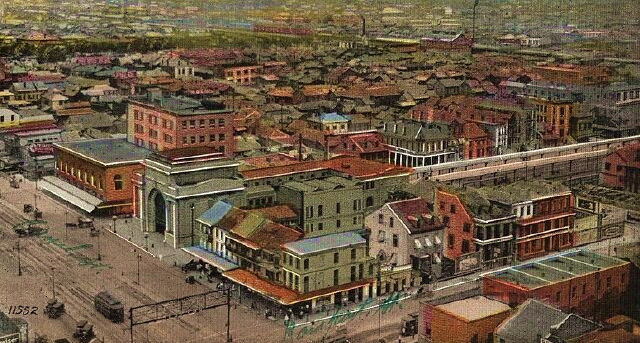

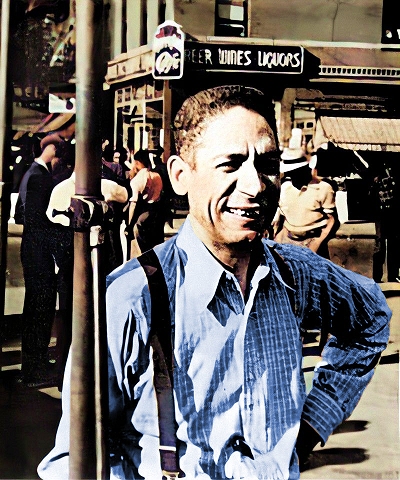

Growing up on Frenchmen Street a bit outside of the French Quarter, Ferd was just a streetcar ride away from many New Orleans musical venues located in the Quarter and the Tremé, as well as downtown. Considered a true Creole, he was a mulatto, which created its own set of difficulties, as the darker communities did not always accept light skinned blacks, yet they were still too black for the white communities.

Ferdinand got past this by communicating through music. He learned guitar at age 7, and piano at 10. As of the 1900 census the family was located in New Orleans with Ferd's half-sister Eugénie Amède added to the home in late 1897. Another sister, Frances a.k.a. Mimi, arrived in mid-1900. Ferd moved out of the Mouton home the following year, residing with his godmother Laura Hunter (a.k.a. Eulalie Hécaud) for some time.

|

Ferd took piano lessons from local black schoolteacher Rachel D. Moment for an indeterminate period of time. Morton described her as "the biggest ham of a teacher that I've ever heard or seen..." However, with his innate talent he also likely absorbed a lot of the influence of other musicians playing in or near downtown New Orleans. Among those he later cited was Mamie Desdunes (a.k.a. Mary Celina Desdunes Dugue), who played a simple blues style due to a crippled right hand. He also mentioned Tony Jackson and Albert Carroll, and by some accounts claimed to have heard or possibly known the storied but somewhat notorious trumpeter Buddy Bolden. In his teens, Ferd became, be his own account, one of the most renowned pianists in Storyville, the red light district of New Orleans set up by alderman Sidney Story in 1897. There is some evidence, or lack thereof, to counter this bodacious claim, but there is little doubt that he spent some time either playing or listening to others play in the houses there. His later description of Tony Jackson playing a Naked Dance for the girls to show off their wares to the customers provides some credence to this probability. Another place he frequented was the Frenchman's Café where many New Orleans musicians played during and after hours.

In early 1904, Morton traveled to Saint Louis, Missouri, allegedly to attempt to play at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, likely on the mile-long amusement Pike, and to absorb local musical influences. There was a contest there in late February at Tom Turpin's Rosebud Saloon that Morton claims he demurred from due to the presence of some of the high-caliber pianists playing there. They included the champion of the event, Louis Chauvin, his friend Sam Patterson, Charles Warfield and Joe Jordan among others. Perhaps the point should be made that he was not yet 14 years of age played, which likely a bigger factor in the overall situation. Still, he soaked in the influences of this environment, learning more than just the music, but also the lifestyle of these pianists.

In 1906, Ferd's mother Lizzie died from a form of heart disease, leaving him more or less on his own at age 16, save for his godmother Laura. During this period Morton also learned more about performance with ensembles while traveling with Billy Kersand's Minstrels throughout the South and Midwest. He also met many musicians that influenced his style and his attitude, which might eventually be described as appropriately confident if mildly cocky. Among them were the aforementioned Tony Jackson, future composer Spencer Williams, John and Benjamin Spikes, Sammy Davis [a pianist and entertainer who was not same as the father of entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr., Samuel Davis, who was born in 1900, so too young], Arthur F. "Baby" Seals, and two gentleman that likely influenced the names of two of his important works, Porter King and Benson "Froggie" Moore. He also learned much of the reality of being a man of color away from his home town who which had been more tolerant of race, which was a hard lesson. During this time Ferd witnessed at least two disturbing lynchings of black men.

Building a Reputation - What's In a Name?

Still tethered somewhat to his godmother's home in New Orleans, it was there in 1910 that Ferd met Billy and Mary McBride, who had their own unique theatrical troupe called Mack's Merry Makers.

He played in their shows for a while, and during the tour frequented some of the brothels along the gulf coast of Louisiana and Alabama, possibly into Florida. Another actor and writer Ferd worked with was Sandy Burns, who for some time had traveled with Sammy Davis. It was allegedly Burns who either gave, or perhaps influenced the origin of, his unique nickname, "Jelly Roll." In the colloquial of the time, the connotation of that name was clearly sexual, and commonly referred to by both heterosexual and homosexual performers, including Jackson who was openly gay. Specifically, it was a reference to the male member, and not so much to a pastry. Just the same, Morton quickly adopted the name, and before the mid-1910s, while he still used Ferd from time to time, he started to enjoy billings as "Jelly Roll" Morton.

|

From this point on, Morton lived the ultimate itinerant pianist's life, traveling from town to town, carousing with local women, hustling in pool halls, and taking in the culture wherever he went. Lessons, or perhaps they should be called skills, that he learned in his early travels were how to be a successful pimp, a pool sharp and card sharp, and how to charm certain people while ticking off others, skills that served him well at various times. He was also a young man of contradictions with his own sense of questionable morality, being both a Catholic and a believer in the bayou culture of voodoo. Morton quickly learned how to turn any insecurity he had into a situation into bravado and vanity, often deflecting anything he thought might be a threat to him or his ego. [Note that these are collective observations noted by many of Morton's peers as well as his original biographer, Alan Lomax, but that they ring true overall through many of his actions, even if they cannot be completely construed as "fact."]

As a result of his constant travel, Morton was difficult to locate in the 1910 enumeration. Some of his movements of this period are suggested by combining his later recollections of who he played with and where with newspaper accounts of those people and events. In 1911 he was associated for a while with William Benbow's as they traveled the south, likely as both a pianist and a singer. The following year he was, at times, working with the Spikes brothers in the Midwest, with who would later pen one of his more iconic pieces. Later in the year and into 1913, he worked with the Jenkins and Jenkins troupe, which included Baby F. Seals, who had recently had his historic early blues piece Baby Seals Blues, arranged by Artie Matthews, published and distributed. Much of 1913 was spent in Texas, and Morton was listed in the Houston, Texas, directory for that year. Ferd had also taken on a vaudeville partner and singer, Rosa Brown, who was usually booked as Rosa Morton, although there was no official record found of them having married. They worked the vaudeville circuit from 1912 into 1914.

Early in 1914, Morton had been working with McCabe's minstrels when they were disbanded during a stay in Saint Louis, Missouri. From there, he and Rosa tried to find another troupe, and ended up in Kentucky by the spring, then back to the Dayton, Ohio area. Ferd, now consistently billed as "Jelly Roll" or "New Orleans Jelly Roll," was receiving excellent reviews for his vivacious style, even when accompanying Rosa. He played a wide range of pieces from piano rags to classical pieces, and by this time, perhaps some of his own compositions. The couple, playing with other notable acts, also played Detroit, Michigan, and ventured down into Indianapolis, Indiana, then back east to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By late summer they were playing in Chicago, Illinois, where Ferd would later spend a considerable period of time. For 1915 he remained there through the remainder of 1914 and into 1915. There is a probability that he also did a short stint with the Memphis, Tennessee band of W.C. Handy, a composer whom he highly regarded at times, and derided in later years.

Ferd, now consistently billed as "Jelly Roll" or "New Orleans Jelly Roll," was receiving excellent reviews for his vivacious style, even when accompanying Rosa. He played a wide range of pieces from piano rags to classical pieces, and by this time, perhaps some of his own compositions. The couple, playing with other notable acts, also played Detroit, Michigan, and ventured down into Indianapolis, Indiana, then back east to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By late summer they were playing in Chicago, Illinois, where Ferd would later spend a considerable period of time. For 1915 he remained there through the remainder of 1914 and into 1915. There is a probability that he also did a short stint with the Memphis, Tennessee band of W.C. Handy, a composer whom he highly regarded at times, and derided in later years.

Ferd, now consistently billed as "Jelly Roll" or "New Orleans Jelly Roll," was receiving excellent reviews for his vivacious style, even when accompanying Rosa. He played a wide range of pieces from piano rags to classical pieces, and by this time, perhaps some of his own compositions. The couple, playing with other notable acts, also played Detroit, Michigan, and ventured down into Indianapolis, Indiana, then back east to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By late summer they were playing in Chicago, Illinois, where Ferd would later spend a considerable period of time. For 1915 he remained there through the remainder of 1914 and into 1915. There is a probability that he also did a short stint with the Memphis, Tennessee band of W.C. Handy, a composer whom he highly regarded at times, and derided in later years.

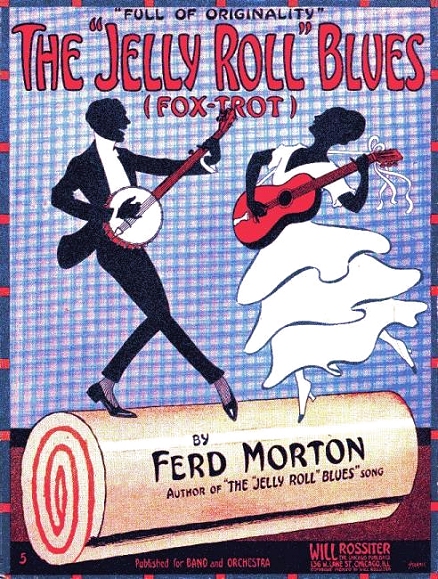

Ferd, now consistently billed as "Jelly Roll" or "New Orleans Jelly Roll," was receiving excellent reviews for his vivacious style, even when accompanying Rosa. He played a wide range of pieces from piano rags to classical pieces, and by this time, perhaps some of his own compositions. The couple, playing with other notable acts, also played Detroit, Michigan, and ventured down into Indianapolis, Indiana, then back east to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By late summer they were playing in Chicago, Illinois, where Ferd would later spend a considerable period of time. For 1915 he remained there through the remainder of 1914 and into 1915. There is a probability that he also did a short stint with the Memphis, Tennessee band of W.C. Handy, a composer whom he highly regarded at times, and derided in later years.Working in Chicago with occasional travel to surrounding areas, Morton was no longer featured with Rosa, who had gone her own way, but worked with, among others, comedian and dancer William "Bojangles" Robinson. It was in Chicago that Morton's first big hit emerged in published form. His self-titled Original Jelly Roll Blues, issued in late 1915 by the well-established publisher Will Rossiter, created some issues before it was in print, in terms of arranging it in a way that was playable by the average pianist while retaining Morton's unique performance style. It would soon be made into piano rolls, recorded to disc, and even mentioned in a later song by Chicago composer Shelton Brooks, most famously as a line in his Darktown Strutter's Ball from 1917. "I'm gonna dance off both my shoes, when they play those Jelly Roll Blues, tomorrow night at the Darktown Strutter's Ball." By that time, Ferd's reputation for his playing and his vivacious personality, both good and suspect, was well established among his peers, and was gaining traction with the public.

According to some newspaper reports, as well as narrative from Barbary Coast pianist Paul Lingle, Morton made some of his first West Coast appearances during the latter part of 1915 at the Pan-American Exhibition (World's Fair) in San Francisco, California. As there was a similar event held in San Diego, California, near the Mexican border, at that time, it is possible that Morton also appeared in Southern California, but that was sketchy to confirm at best. Morton circulated around the Midwest in 1916, sticking largely to Indianapolis, Saint Louis and Chicago. However, he apparently enjoyed California, or at least found that the dearth of professional pianists of his caliber in the state provided him some golden opportunities, and eventually migrated out to Los Angeles in late 1916 or early 1917, possibly following the lead of bandleader William Manuel Johnson and his sister Anita who moved there at the same time.

Rise To Fame and Legend - The West Coast

One of the first locations where Morton set up was the Cadillac Café in Los Angeles in the spring of 1917, where he would play through most of the year. Before Morton came out, Los Angeles, California, was a rather unremarkable location during the bulk of the ragtime era. Very little published ragtime emerged from that city in the 1900s and 1910s, and most of the contemporary piano music of that period was presented on the vaudeville stage, in addition to popular songs and old favorites. The bulk of ragtime pianists and showmen were up north working the Barbary Coast section of San Francisco and the Bay Area, and even up into Seattle, Washington.

However, at the beginning of the jazz age, just before and around the time of Morton's arrival, there was surge of contemporary popular instrumental music in Southern California, which coincided to some degree with the growth of the film industry there, which was at a highly-accelerated pace from 1913 to 1920.

|

After several months at the Cadillac, either as a soloist or with local ensembles or singers, Morton decided to bring a taste of home to the city. In early 1918 he formed his Creole Jazz Band comprised of several fellow New Orleans musicians, including Mack Lewis on the Clarinet, Buddie Petit on trumpet, Willie Moorehead on trombone, and a pianist/clarinetist, Dink Johnson, on drums. Dink was Anita and William Johnson's brother. He had actually played the clarinet with trombonist Edward "Kid" Ory's band prior to his west coast migration. He would later play a somewhat important role in Morton's life near the end. Johnson's piano playing in particular would be audibly influenced by Morton, as later recordings and compositions would attest.

In the winter of 1918 the group played near the Mexican border in San Diego, and also may have made excursions at times into Tijuana, albeit more for recreation and to soak in the culture than anything else. At this juncture it should be noted that quite a few of Morton's pieces written throughout his career had what many called a "Spanish tinge" applied to them. This could be analyzed as mildly syncopated melody over constant habanera bass line (not "tango" as some have mislabeled it). Even though Morton clearly spent time in Tijuana and parts of Northern Mexico, that influence most likely came from his home town. From the 1880s into the early 20th century, traveling mariachi bands would work their way from Mexico through Texas and over to the Gulf Coast, so they were often heard playing their Latin-tinged pieces in New Orleans. Some have claimed that they helped influence jazz in that town simply by selling of their instruments, including trumpets and guitars, so they could afford passage back home. While this may be possible, that they influenced several Southern musicians is clear, and that "Spanish tinge" feeling was clearly embedded in Morton throughout his composition career.

By spring of 1918, the Creole Jazz Band (sometimes Orchestra) was back in Los Angeles. Among Morton's friends there was the notorious singer and nightclub entrepreneur Ada "Bricktop" Smith, who had already made waves in Chicago, and in the 1920s would forge her way to more fame in Paris, France, with her famous clubs being the talk of the continent. In May, Morton had one of his first renditions of the somewhat malleable Frog-I-More rag copyrighted. It would be one of his better-known standards for the next two decades. He also allegedly composed and became known for his thoroughly Spanish-tinged piece The Crave during this era, but whether this is factual is unclear, since Morton did not leave any clear evidence of this piece until at least 1938.

Still in Los Angeles near the end of the ongoing war in Europe, Morton, as most men born in the early-to-mid 1880s, was called on to register for the final draft call on September 12th. The information on the card raises some questions and confusion. Ferd gave his permanent address as still in Chicago, his career as Actor rather than musician, and his employer as the Levi Circuit (actually an independent vaudeville organization run by Bert Levey) in San Francisco. The birth date shown was September 13, 1884, which is also a bit perturbing. He also listed a wife living in Los Angeles, but as "Mrs. F. Morton."

The lady in question was the Johnson brothers' sister, Anita, who went by Juanita Gonzalez, but not Morton. She was a very fair-skinned mulatto creole who at times was able to pass for white. At some point Ferd claimed that he and Anita had been married as early as 1909.

It is possible that he had known Anita that far back while in New Orleans, but no official record of either a marriage or divorce has been located, so they were probably referring to a common-law marriage situation, much as Morton's birth parents were in. In spite of another questionably legal marriage in later years, Morton ultimately devoted much of his love to Anita, and depended on her when times were tough. She was clearly his anchor, even if at times he may have considered her his bane as well. During their early years in Los Angeles, Anita ran a hotel with some occasional help from Morton. Although she was a singer, she claimed that Ferd never let her perform with his band. But, as per what she told jazz historian Floyd Levin in 1950, he clearly cared for her, as Anita later noted that Morton did not want her to do the work required to run the hotel, instead hiring others to clean the rooms and run the front desk.

|

In 1919 Morton was on the move again, literally, as there were reports he had sunk some of his earnings into a large twelve-cylinder touring car, making most likely either a National or a Packard. After a stint in San Francisco for the winter and spring, he traveled up to Vancouver, Canada, playing for some of the summer and fall in a jazz band led by pianist and clarinetist Oscar Holden. They were likely playing in the Patricia Café in the hotel it was named after. Bricktop also joined them for a while. He allegedly also worked as a pimp during this period, but that is possibly more legend than fact. The band continued into 1920 and 1921, but Morton was restless and moved on near the end of 1919, back to the United States, into what would be a much different environment than he had enjoyed over the last decade and more.

The culprit was the vile (to many) Volstead Act, which was the enforcement vehicle for National prohibition of alcohol. New Orleans had already been dealt a blow in 1917 when the United States Navy, in an effort to keep their sailors safe and less distracted when in port, shut down Sidney Story's famed district, thereby partially ridding the city of a fairly good tax base supported by the lucrative business of prostitution. Now, the government, or more rightfully, a majority of the citizenry, decided to do away with the manufacture and sale of alcohol (albeit not the consumption, a major loophole), which was one of the drawing points of music establishment, in addition to the music itself. While all may have seemed lost at that point, the Volstead Act made alcohol more popular than ever, and the excitement of doing something not quite legal with a group of like-minded people to the wild sounds of a driving band or a blues group was just too irresistible to resist. So it was that Morton started playing in the Pacific Northwest in 1920 in Seattle and Portland in cabarets that more often than not added some coffee or tea in with their scotch. It could have been a moral disaster (depending on one's view of morality), but the alcohol and music business was soon booming again, and performers like Morton provided some of the "jazz age" soundtrack that went along with the grand experiment.

Ferd appears to have stayed up in the Northwest through at least the summer of 1920, one of his stops being the Entertainer's Café in Seattle, and perhaps back to the Patricia now and then. Down in Los Angeles, from which a somewhat weekly report emerged in the Chicago Defender by way of "letters" from musician "Ragtime" Billy Tucker, the Spikes Brothers were running their So Different Music House on Central Avenue, where the core of black life was located in that city. The sold sheet music, instruments and phonographs, and even did a bit of publishing of their own works. Among those released in early 1920 was Some Day Sweetheart, which would become associated with Morton within the next few years.

The status of Cadillac is unclear, but it appears to have closed its doors shortly after the onset of prohibition. The big venues now in Los Angeles were the Dreamland, a popular name for band venues around the country in the 1920s, and the similarly-named Paradise Gardens dance hall, another growing hot spot. Morton would make his way down there soon enough. But he was also being lured by another intriguing spot south of the border.

|

After bouncing around the west coast for most of 1920 and early 1921, Morton resituated himself with Anita back in Los Angeles in the late spring of 1921, and engaged his orchestra into the Paradise Gardens. They spent the summer there drawing big crowds, which according to one advertisement included some of the increasingly popular crop of "movie stars" from the Hollywood studios. For part of the summer, Jelly Roll's "Famous Creole Band" shared the venue with the Black and Tan Orchestra. The Spikes Brothers had expanded their empire as well, opening up a leisure park with amusements for "members of the Race" at Leake's Lake near the Watts neighborhood just south of downtown, calling it Wayside Amusement Park. It had become a true melting pot of African-Americans, Japanese, Asians, Mexicans, Irish, and many others, so a popular spot for boating, recreation and ja. Then in the fall came the alluring call from down south.

Tijuana (a.k.a. Tia Juana), across the U.S./Mexico border from San Diego, was enjoying new-found popularity, in part because they didn't suffer from the restrictions of the Volstead act, and actually from a number of other allegedly repressive morality laws. There was a cry for entertainers to work down there for good money in cheap living situations. Musician Eddie Rucker made his case, and in the fall a few musicians followed. Morton applied for and received one-year visas from both California and the Mexican consulate allowing him to work in Tijuana as a musician. Whether Anita went with him or remained in Los Angeles running her establishment is unclear, but she likely made a few trips at the very least. It was also a popular spot with Hollywood royalty, and many went down to see bullfights, gamble in the casinos, or simply drown their sorrows while escaping the rigors of fandom.

There is one story that soon after he started his tenure in Mexico that Morton and his orchestra were engaged to play at the prestigious U.S. Grant Hotel, named after the Civil War general and U.S. President, situated in San Diego. The gig in November, 1921, was purportedly arranged by Dink Johnson, but did not last long, albeit for unclear reasons. Johnson stated that the group was fired by management because Morton crossed his legs at the piano. The more likely story, as told by Morton, was that there was a white band playing elsewhere in the hotel and he discovered they were getting twice what his group was, so he pulled his group out and headed back across the border. Throughout the next several months Morton and his group would divide their time between Tijuana and Los Angeles, sharing the stages with a growing number of Negro jazz bands rivaling the level talent currently heard in Chicago and New York City.

By the early spring of 1922 it was announced that Morton and his band were signed for a tour on the Pantages Theater circuit, although it may have been a relatively short trip with just a few nights in each location. Within a month Tucker wrote that Morton was now managing the Wayside Amusement Park performance venue, and his six-piece band was playing there four nights a week. Near the end of April Morton's venue received a visit from no less than Chicago's current jazz champion, Joseph "King" Oliver. He reportedly set the town on fire with his brand of trumpet playing. Ferd and his band held their own reign over Wayside through the summer months, although give that it was considered a respectable establishment and a largely outdoor venue, it is unclear if alcoholic beverages were offered on a regular basis. In July, Morton's friend "Kid" Ory brought his band to Los Angeles where they made some recordings at the Spike Brother's studio, and played on the radio, reportedly the first black jazz band to do so in Southern California. They stayed there into the fall. In September, Morton took his band on a short Southern California tour outside of Los Angeles, some of it in San Diego and back to Tijuana. Then the tenure in Tijuana became tenuous.

Morton, according his interviews with Lomax, had already experienced an unfortunate incident with the law when he was briefly suspected in the slaying of a grocery store clerk in early January of 1923. In the end, arrests were made of two other black men, but it may have shaken him just enough to where he retreated back to Tijuana for a while. Then, in an unfortunate incident in early February, an American black man named Chester Carleton who was staying in Tijuana lent his car to a friend to take it to San Diego for the day. The car was in a collision with some $250 damage assessed. Carleton argued with the man, George Monteverde, and gunplay was initially diffused by a San Diego sheriff. However, they finally had a showdown just across the border on a bridge over the Tijuana River when Carleton fatally shot Monteverde, inciting a good-sized riot in the streets, and false reports of his lynching. Even though Carleton was assured he would have a fair trial, there was clear dissension against the black population, and many of them, including Morton, high-tailed it back to the North, either to San Diego or Los Angeles, not to return all that very soon.

Many of the musicians, including Ferd, sought to stage a benefit concert and dance in mid-March to raise money to buy Carleton's freedom. In spite of their best efforts to get the necessary $15,000 bond, they managed only $283.50 for that evening. This was Morton's last hurrah in Los Angeles for nearly two decades, as he would soon leave Southern California, Mexico, and his long-time love and common-law wife Anita behind, heading to where the current nexus of jazz was having a decidedly national impact - Chicago, Illinois.

Chicago, The Red Hot Peppers, and "Jelly Roll" Style

In April of 1923 Ferd found himself back in Chicago with a well-rounded résumé. It is unclear how many members of his prior orchestras and bands joined him there, but even if it was none, Morton's reputation both as a performer and composer (and a number of other disciplines) was enough to attract new talent to his side. Although only a couple of his compositions were actually in print, they had been heard by many, and would soon find their way into circulation. One of Morton's concerns was allegedly that if his style was too closely emulated in print that others might catch on to it and give him unwanted competition. But there was also the demand, and the promise of income that sheet music sales could bring. So it was that some of the early Chicago issues of Morton pieces were either simplified or simply made a bit more generic, providing a framework for his chord and melodic structure without revealing too many of his tricks.

In addition to publication, Ferd thought it was about time that he had his style heard in more than just local venues, and sought out a record company that would take him on.

According to a later memoir by blues composer and musician Perry Bradford, Morton asked him by way of a letter sent from Fort Wayne, Indiana, if Bradford might be able to get him some recording dates in New York. Perry had a better idea, which was to go to Richmond, Indiana, to see Harry Gennett, who would probably accommodate him.

|

Gennett records was founded in 1917 by three brothers, Harry, Fred and Clarence Gennett, managers of the Starr Piano Company of Richmond, Indiana. Their initial studio was set up in New York City, but in 1921 they installed a rudimentary acoustic recording studio on the grounds of their Richmond factory. Even if the aural quality of their product was less than sufficient, the talent they attracted, being one of the first Midwest studios to record and distribute the work of black artists, was often stellar. This included the bands of King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, and, in 1923, Morton.

Although he had cut two sides for Paramount Records in a Chicago studio a month prior, his first recordings of note were laid down in Richmond in July, including several with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. Some of them included his own compositions and arrangements. The sound quality was perhaps less than Morton would have wanted, but at least now his music was available to the average consumer, both black and white, and it laid the groundwork for a more lucrative future in records, especially after the advent of electrically-recorded sound. This session was followed later in the year by one at OKeh Records in Chicago.

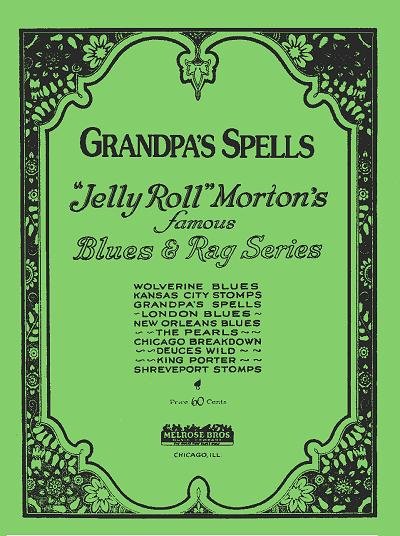

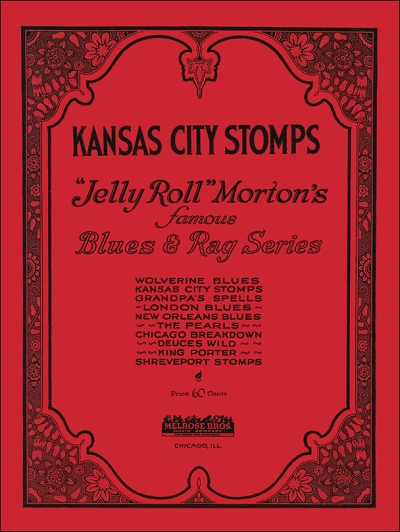

In order to obtain legal copyright protection and provide add-on sales through sheet music, Ferd went to the Melrose Brothers publishing company in Chicago, joining their writing and arranging staff. The company was started around 1920 by Walter and Lester Melrose, both of them important white supporters of black music in Chicago. The brothers would also take on works by Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong, calling them "staff writers" as they did with Morton. They also tended to add lyrics to tunes in an effort to collect their own royalties on the songs, but can be forgiven this for the exposure and support they gave to many black composers of jazz.

The brothers would also take on works by Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong, calling them "staff writers" as they did with Morton. They also tended to add lyrics to tunes in an effort to collect their own royalties on the songs, but can be forgiven this for the exposure and support they gave to many black composers of jazz.

The brothers would also take on works by Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong, calling them "staff writers" as they did with Morton. They also tended to add lyrics to tunes in an effort to collect their own royalties on the songs, but can be forgiven this for the exposure and support they gave to many black composers of jazz.

The brothers would also take on works by Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong, calling them "staff writers" as they did with Morton. They also tended to add lyrics to tunes in an effort to collect their own royalties on the songs, but can be forgiven this for the exposure and support they gave to many black composers of jazz.The material that the Melrose Brothers issued in 1923 and 1924 alone was comprised of some of Morton's most memorable, and over time, most played works. Morton's style was unique and emulated by many pianists, although rarely duplicated. Even in printed form it had a bounce to it, and he used many chord inversions instead of expected chord placements. His music was also more instrumental in nature, as even though he had played and recorded with many groups, he was able to imitate various instruments in his solo playing. Walter Melrose was also instrumental in making sure Morton's Gennett sessions went well, both helping to set them up as well as supporting proper rehearsal time. They routinely used the records to promote their sheet music, and vice-versa.

Grandpa's Spells, a piano rag, was one of Ferd's early favorites. He was proud of the fact that with little effort (on his part, of course) it could be played as a rag in a café, but then turned around as a lively one-step or two-step at a society party with his orchestra. Kansas City Stomps was a great demonstration of not only his bounce, but his propensity to start a trio with a slight but dramatic pause in the action. Mr. Jelly Lord made for a great salacious blues performance, while Stratford Hunch had a sense of humor embedded in its composition. The Pearls was a piece that Morton claimed was one of the most difficult jazz numbers ever written (a bodacious and suspect claim, given what has emerged since the 1940s), but with one of the more memorable trios.

There were two of these early numbers which found wide acceptance and acclaim, as well as performances on piano rolls and by bands around the United States. First was the King Porter Stomp, which was likely an homage to Porter King, whom Morton claimed was a Gulf Coast musician that he considered a dear friend and early influence. While King's identity has been challenging to historians, the piece has continued to enjoy a measure of fame in every decade since it was first published and recorded. Then there was The Wolverines, also known as the Wolverine Blues in song form.

Given the popularity of this creature as the official mascot of Michigan (embraced more so since the piece saw a measure of fame), it remains one of the most frequently played Morton pieces of that era in the guise of piano solos, duets, jazz bands, and even orchestras. Other notable works, such as Perfect Rag and the best of the Spanish-tinged pieces, The Crave, were likely composed and performed even before 1923, but did not find their way onto records or in print until the 1930s and 1940s.

|

Of course, being that Morton was in the jazz-crazy booze-flowing flapper-happy town that "Billy Sunday could not shut down," he and his band had little trouble finding steady engagements in and around Chicago, including regional locales such from Milwaukee, Wisconsin to South Bend, Indiana. One of the hot spots in the latter town was the Tokio Gardens dance hall, about which several advertisements concerning Morton's groups appeared in late 1923 and early 1924. Other gigs followed as far off as Ohio, including one that would have some lasting impact.

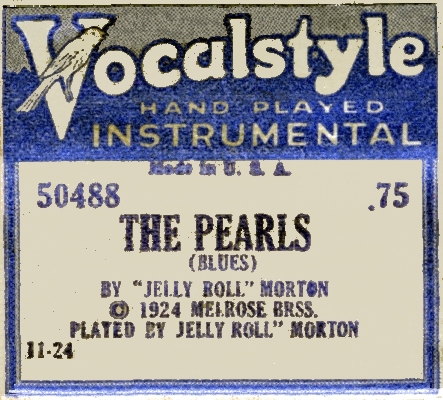

Much as they had arranged for Morton's audio recordings, the Walter Melrose also hooked Morton up with the Vocalstyle piano roll company in Cincinnati, Ohio, in mid-1924. They had been supposedly the first company that put lyrics on their piano rolls, and during the peak of the player piano craze in the early 1920s (eventually killed by the phonograph, and then radio), Vocalstyle was one of the more important roll manufacturers. They were able to capture thirteen Morton performances on mark-up rolls. According to the late historian Mike Montgomery, Vocalstyle cut the rolls more or less as Morton performed them with virtually no editing, except for perhaps some missed notes. They created alternate takes in a sense to Ferd's Gennett and OKeh records, since he tended to make each performance different. However, after the sale of Vocalstyle to Q.R.S. in 1926, followed by the decline of the piano roll business in the 1930s, many of Morton's rolls disappeared, and only recently have collectors have been able to find nine of the thirteen performances. Over the next two years Morton would cut a handful of rolls for both Capitol and Q.R.S., expanding his legacy even further with engaging performances, but would stick to recordings from 1926 forward.

However, after the sale of Vocalstyle to Q.R.S. in 1926, followed by the decline of the piano roll business in the 1930s, many of Morton's rolls disappeared, and only recently have collectors have been able to find nine of the thirteen performances. Over the next two years Morton would cut a handful of rolls for both Capitol and Q.R.S., expanding his legacy even further with engaging performances, but would stick to recordings from 1926 forward.

However, after the sale of Vocalstyle to Q.R.S. in 1926, followed by the decline of the piano roll business in the 1930s, many of Morton's rolls disappeared, and only recently have collectors have been able to find nine of the thirteen performances. Over the next two years Morton would cut a handful of rolls for both Capitol and Q.R.S., expanding his legacy even further with engaging performances, but would stick to recordings from 1926 forward.

However, after the sale of Vocalstyle to Q.R.S. in 1926, followed by the decline of the piano roll business in the 1930s, many of Morton's rolls disappeared, and only recently have collectors have been able to find nine of the thirteen performances. Over the next two years Morton would cut a handful of rolls for both Capitol and Q.R.S., expanding his legacy even further with engaging performances, but would stick to recordings from 1926 forward.Throughout the period of 1924 into mid-1926, although based in Chicago, Morton and his band went on several tours of parts of the country, even appearing on radio from time to time in a variety of studios. They cut more sides for Gennett, and also for two other recording studios, the resulting discs which were distributed by several labels. The Walter Melrose was more or less faithful in his support of Morton's music, but as per some historians dropped the ball in one regard. Morton could have and should have become a member of ASCAP. However, it was less of a race issue and more of an administrative one that he missed that opportunity, as Melrose was not a member at that time, and he required two ASCAP sponsors and five pieces published by an ASCAP house in order to qualify. This lack of protection would haunt him near the end of his life, but for the time being he was spending his gains on fancy clothes, cars, and diamonds, the latter which he famously had embedded into one of his front teeth. Among his biggest numbers released during this period was Milenberg Joys, composed with two associates of Morton. In the spring of 1926 Morton some solo sides for Vocalion Records, many that rivaled his 1924 solos for Gennett, but recorded with much better quality.

In spite of his continuing success, one other big break that had evaded Morton was a major record label to better record and distribute his works. That was finally resolved in part by Walter Melrose, when with his assistance in mid-1926, Morton was signed to the Victor Talking Machine Company for a four-year contract. Arguably the best of the Morton records of the 1920s were those cut with his own band, the famous Red Hot Peppers. The first set of sides from the fall of 1926 were recorded using the Western Electric Orthophonic system, one of the best of that period. They were cut in the ballroom of the Webster Hotel in Chicago, a popular spot both for recording and radio broadcasts. The Morton tracks on Victor have since become legendary, and even as they were originally released quickly became best sellers for the important Victor catalog. Many of the tracks were re-recordings of tunes he had done with Gennett, Okeh, Vocalion and other labels. However, given his propensity for playing something a bit differently every time, and that Victor was recording his work with microphones instead of acoustic horns, it was worth reprising all of these works. Extant multiple takes of some of the tracks reveal differences not only in Morton's performances but also those of his band.

They were cut in the ballroom of the Webster Hotel in Chicago, a popular spot both for recording and radio broadcasts. The Morton tracks on Victor have since become legendary, and even as they were originally released quickly became best sellers for the important Victor catalog. Many of the tracks were re-recordings of tunes he had done with Gennett, Okeh, Vocalion and other labels. However, given his propensity for playing something a bit differently every time, and that Victor was recording his work with microphones instead of acoustic horns, it was worth reprising all of these works. Extant multiple takes of some of the tracks reveal differences not only in Morton's performances but also those of his band.

They were cut in the ballroom of the Webster Hotel in Chicago, a popular spot both for recording and radio broadcasts. The Morton tracks on Victor have since become legendary, and even as they were originally released quickly became best sellers for the important Victor catalog. Many of the tracks were re-recordings of tunes he had done with Gennett, Okeh, Vocalion and other labels. However, given his propensity for playing something a bit differently every time, and that Victor was recording his work with microphones instead of acoustic horns, it was worth reprising all of these works. Extant multiple takes of some of the tracks reveal differences not only in Morton's performances but also those of his band.

They were cut in the ballroom of the Webster Hotel in Chicago, a popular spot both for recording and radio broadcasts. The Morton tracks on Victor have since become legendary, and even as they were originally released quickly became best sellers for the important Victor catalog. Many of the tracks were re-recordings of tunes he had done with Gennett, Okeh, Vocalion and other labels. However, given his propensity for playing something a bit differently every time, and that Victor was recording his work with microphones instead of acoustic horns, it was worth reprising all of these works. Extant multiple takes of some of the tracks reveal differences not only in Morton's performances but also those of his band.Among the most memorable of the Victor recordings done by Morton in Chicago was Black Bottom Stomp, equally as engaging as a band number as it was for solo piano. Sidewalk Blues was also unique for some off the beat percussion, and an opening and closing that included some sidewalk chatter and street sound effects to boot. One of Joe Oliver's numbers was included in the mix with a substantially hot take, that being Doctor Jazz. He also covered the Spikes Brother's song Someday Sweetheart, a recording for which he would be known for some time. Even though he was sharing the spotlight with Oliver, Armstrong, and other black performers of the period, Ferd and his group held their own during the peak of the jazz age. They also found a lot of traction in England on Victor's sister label, H.M.V. (His Master's Voice), garnering good reviews in the United Kingdom and Europe. The next set of records made in June of 1927 fared equally well, with some of the standouts being Wild Man Blues and the increasingly popular Wolverine Blues.

It is curious that given his contract with Melrose to write and arrange, as they copyrighted his pieces and published many of them during his five year contract from 1923-1928, that he rarely got arrangement credits on anything, particularly on his own pieces. There has been discussion about whether some of the charts were made before or after they were recorded, as some of them appear to closely emulate what made it to disc. The general consensus seems to be that Morton was a competent arranger overall, and that many times the recordings were done directly from his charts with little variance in the instrument performance other than the piano.

However, it may have been a business decision by Walter Melrose in terms of distribution of funds that kept Morton's name from having more prominence outside of composer credits.

|

Morton did play with a few other musicians on Chicago recording dates from 1926 to 1928, including a few for Columbia with Johnny Dunn. However, he was usually better as a leader rather than a side man, and his best work was with his own groups. They included subsets of his band as well as the full group with the occasional shift in personnel. As the group rose in their popularity, which was publicly with black audiences and to some extent privately with white audiences who would buy the records but not always frequent the events, The Red Hot Peppers continued to tour the eastern half of the country from Buffalo, New York and Ontario, Canada, back to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the latter location they famously took over the Alhambra Theater during the late summer of 1927 before extending their reach into the state of Iowa. While Melrose had been responsible for Morton's music rights to that time, Morton had engaged representation in New York City, possibly through Victor, and for a while was managed by the Music Corporation of America (M.C.A.). His five-year contract with Melrose ran out in the spring of 1928, and future pieces were rarely copyrighted through the rest of his life, and even fewer would find their way into print until the 1940s.

Many of Morton's peers were enjoying an equal measure of success in 1927 and 1928, including Joe Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, and Duke Ellington, the latter who would soon reign over the music scene of Harlem in New York City. In the late 1920s, in fact, there was a geographic shift as the center of gravity of hot jazz moved from Chicago to New York. The latter was building better clubs and theaters, had a wider reach with radio in the early days of networks, and some of the better recording studios and engineers. In the spring of 1928 Morton took his group to New York City for performances at Danceland and other venues, and in June recorded six sides at the Victor studios, likely his first sides done in New York with his band. However, his stop there was only temporary, as the band continued on a scheduled tour throughout the rest of the year, focusing more on the East and Mid-Atlantic states rather than the Northeast and Midwest.

The part of Morton's life that had been missing, or at least largely neglected since he left Los Angeles, was Anita, although there was no indication they were ever legally married. She had more or less been abandoned when he left for Chicago. There was likely a string of other women in his life for the next several years.

However, in 1927, Ferd met showgirl Mary Mabel Bertrand. A New Orleans native who was just a couple of years older than Ferd, Mabel was already married when Ferd met her, probably for the second time, and had been playing and singing in a number of stage plays, musicals and nightclubs in Chicago, New York, and the east during the mid-to-late 1920s. According to collected information, which is sketchy in some cases, Mabel and Ferd became involved in either Chicago or Kansas City, Missouri, when they started to cohabitate. Mabel claimed that she and Morton were married by a justice of the peace in Gary, Indiana, in November of 1928, although documentation of such a union has been evasive, and therefore questionable. Just the same, Mabel used the name Morton for many years, including on her Social Security Card application in 1943. From 1928 for at least part of the next decade, Mabel was Morton's companion as they traveled the country.

|

Much of the winter and spring of 1929 was spent in New York State and Pennsylvania playing for dancing throngs. After a Fourth of July appearance in Pittsburgh, Morton and his band traversed eastward across the state to Philadelphia. On July 8th, 1929, he crossed the Delaware into Camden, New Jersey, where Morton made a series of solo records for what was now R.C.A. Victor, the record company having recently been bought by the Radio Corporation of America. Two more sessions would follow with his group, which on the label was cited as Jelly Roll Morton and His Orchestra rather than their better known name of Red Hot Peppers. Then it was back on the road for more concertizing through much of the East, primarily Pennsylvania where the group had become extremely popular. However, changes were coming, not just for Morton and jazz, but for the entire country. The bubble of Wall Street and American prosperity on leveraged dollars was about to burst, and the timing was not so good for many musicians who had been riding high for most of the 1920s.

New York City - Depressing Times

Moving on, as always, to bigger and better horizons, and following the lead of many Chicago musicians who had found more fame either in Europe or on the East Coast, Morton and some of his band relocated their base to New York City, just ahead of the coming Great Depression. In November and December, just after the stock market crash, Morton and various personnel recorded another set of tracks in the R.C.A. Victor studios in New York City.

Although they ostensibly continued to fulfill contract dates into 1930, Morton appeared to have been possibly looking for something that would keep him more in New York on a steady basis. According to an article in March of 1930 in the Baltimore Afro-American, Morton had set up a dance school and publishing house in mid-town Manhattan in the Roseland Building a few blocks north of Times Square. For the 1930 enumeration, Ferd and Mabel were lodging in Manhattan, New York, just a few blocks from Harlem. Ferd was listed as a theater musician and Mabel as a theater actor, although having trimmed some fourteen years off her actual age.

|

More recordings for R.C.A were made throughout 1930, with sessions in March, April, June and July. Ferd also worked as an accompanist for a couple of singers, and cut a few sides with his associate Wilton Crawley. One of those tracks, Fussy Mabel, was likely written for his self-declared wife. But records weren't selling so well at a time when more people were buying radios and the parts to keep them running. The growing broadcast medium had different content played on it every day, rather than the same old material, and was usually live. During a time of economic hardship radio seemed like the better investment for music fans with dwindling funds. So many piano roll and record companies went out of business, and the larger ones trimmed their belts by going more mainstream in their choices and dropping fringe or niche acts, even if they had their fans. Even sheet music took a substantial hit in the early 1930s. Such was Morton's fate after his October 9th, 1930 session after which his contract with R.C.A. Victor would not be renewed. It would be nearly a decade before he recorded for R.C.A. Victor once more.

As money dried up, so did gigs, in spite of the continuing fame of Morton's band. However, there was a flip side to this from a musically progressive point of view. Band's like those of Fletcher Henderson, Edward "Duke" Ellington and Cab Calloway, all doing well in Harlem and around the East, were moving forward into the 1930s and either adopting or setting new musical trends. Ferd had been experimental to some degree, especially with pieces like Pep and Freakish, but he was, in many regards, still embedded in his world of ragtime, blues and stomps. The recordings of his own works made this clear, even though the band did tackle some newer material by other composers. His playing style was highly unique, but did not adapt well into the age of early swing and radio crooners. Hot music also, to some, was not as appropriate a soundtrack during the Great Depression as was slower blues (which Morton did well), love ballads, and songs pulled from Broadway shows by George and Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin and Cole Porter. To add to this, as was more readily discovered in later years, Morton was either recycling tunes under different names, or simply playing variations on his numbers, figuring to call them something different. [These are noted in the Compositions list with bracketed titles.] This musical paradigm shift made Morton's remaining band, and even himself as a soloist, less viable for radio. Even the live venues were having their own troubles, some not being able to pay well, if at all time.

[These are noted in the Compositions list with bracketed titles.] This musical paradigm shift made Morton's remaining band, and even himself as a soloist, less viable for radio. Even the live venues were having their own troubles, some not being able to pay well, if at all time.

[These are noted in the Compositions list with bracketed titles.] This musical paradigm shift made Morton's remaining band, and even himself as a soloist, less viable for radio. Even the live venues were having their own troubles, some not being able to pay well, if at all time.

[These are noted in the Compositions list with bracketed titles.] This musical paradigm shift made Morton's remaining band, and even himself as a soloist, less viable for radio. Even the live venues were having their own troubles, some not being able to pay well, if at all time.Such was the case when he presented his revue Speeding Along at the Jamaica [New York] Theater in late May and early June of 1931. The management of the theater was extracting funds from the nightly take to cover necessary costs for operation, but his spending got out of control to the point where, according to the New York Age of June 6, he was unable to pay the musicians the $00 he owed them. While the band was still able to find some work in dance venues throughout the East and New England, the payments were less. The advertising often cited Morton as appearing with his "Victor Recording Orchestra" even though they were no longer under contract to the record company. As they continued into 1932, appearing at times with other groups, Morton's name started to show up further and further down the list. Even though they had reigned during the 1910s and 1920s, the Great Depression was hard on musicians of color in the 1930s, and even their union in New York City was hard-pressed to address the problem with any great effectiveness.

By 1933 Morton was more of a fading celebrity than a working musician. His presence at occasional musical events, some honoring other musicians, was noted in the papers. However, his band was no longer extant, some of the members having sought work elsewhere, or even retreating to Chicago or their home towns. When he played out of town it was more often than not with local musicians following his charts. Claims of him playing with the Red Hot Peppers or his Victor Recording Orchestra were only partially true at times, as some of personnel were not involved with the stellar sessions of the 1920s. Performances in 1934 and 1935 were very infrequent, or at least rarely found in newspapers that have survived into the 21st century. Morton eventually distanced himself from many of his peers to the point where he was actually ostracized and outcast by the musician's union that held jurisdiction in New York. He blamed some of the musicians for not wanting to follow his charts, and imbibing at performances. However, Morton was also viewed as singularly difficult to work with, as per an article in the Philadelphia Afro-American of April 11, 1936:

THE MAN WHO REALLY INVENTED JAZZ

IS NOT PERMITTED TO PLAY IT

IS NOT PERMITTED TO PLAY IT

|

It is ironical, but true that the man who really invented jazz is now not permitted to play it.

Jellyroll Morton, who because of his strange piano style, created this modern rhythm, because of his disagreement with the musicians' union is kept out of organized music circles and is prevented from forming an orchestra.

Morton, who now makes his home in Harlem, claims that he was playing jazz long before James Reese Europe and his famous band made that type of music an international novelty during the war.

New Orleans is the home of jazz, according to Morton.

While Jim Europe was busying himself with the musicians' headquarters in making plans to organize a band for the 15th Regiment of the N.Y.N.G a band stole into New York from New Orleans called the Creole Band and played at the Palace Theatre for two weeks and broke all records for attendance.

Sans [sic] piano and drums, they even improved on Jim Europe's ragtime. The owner of the band was William Johnson, brother-in-law of Jellyroll Morton.

Europe went abroad with the 15th Regiment band where he introduced jazz in Europe, with the same results.

Meanwhile Jellyroll Morton set about in earnest to develop this type of music which he called jazz and discovered that it had a much better effect if played in a slower tempo.

He gave the following definition of jazz music: Jazz music is a cross between American ragtime with an inaccurate tempo and Spanish music with an accurate tempo...

With that, Mr. Morton assumes full responsibility as the creator of jazz music: Jazz music is a [sic] still in its infancy...

To further his claim that jazz is not yet perfected, Mr. Morton states that in all instruments there may be obtained, notes so odd and freakish that very few musicians are capable of producing them. Those who have, had no way of recording them because there were no such notes in the musical scale...

The article continued on with information on other famous bands playing in Harlem and New York at that time, but did not provide further details on Morton's exile from organized music, as it were. Just the same, this and continuing financial woes may have been the final straw for Morton in New York City. He had lost most of his assets, including some enterprises he had invested in, and was in disputes with Melrose Music (which was no longer owned the Melrose Brothers) over royalties and his non-admission to ASCAP. Broke and dejected, either out of pride or embarrassment, or very likely just frustration, he extracted himself from New York in May or June of 1936 and moved down to Washington, DC, where he would find himself all but forgotten in the wake of the swing era, which would officially start later that year out in California.

Washington, DC - Obscurity, Then Rediscovery

Mabel, who had remained in New York, later noted that she thought Ferd had moved to the Nation's Capital with the intention of promoting professional fights, and not so much to continue in music. However, without seemingly trying to make a splash, but merely a statement, Ferd walked in to the offices of Washington, DC, broadcast station WOL in mid-June of 1936 and asked for an audition, reportedly without even giving his name, as noted in the Washington Daily News of June 23. Needless to say he passed their audition, and once he announced who he was the lights clearly turned on for most in the place. So for a few days in late June and early July, Jelly Roll Morton gave his own accounting of the history of jazz over the airwaves in Washington. Then he all but disappeared.

Over the next several months, Ferd managed to find work and part-ownership in a downtown Washington D.C. bar at 1211 U Street in the black area of town. Under a variety of names, including The Music Box and The Blue Moon Inn, it was best remember as The Jungle Inn when it was finally "discovered" as it were. Morton went into the partnership with a woman named Cordelia Rice Lyle. The relationship likely went a bit beyond professional as well.

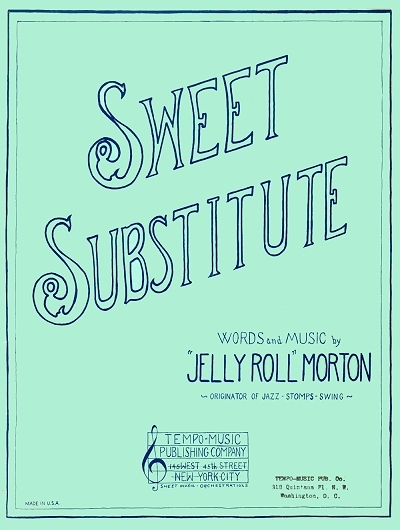

It has been thought that Morton's 1938 tune Sweet Substitute was written for Cordelia or with her in mind. In any case, Ferd was under the radar for some time, known only to local crowds, who came down to hear him play, present little shows, and act as a master of ceremonies for certain events, keeping The Jungle in business to a degree. He was also a bartender, barrel opener and bouncer, taking on many roles that would have seemed unlikely just a decade before.

|

A small note appeared in Down Beat magazine in a May, 1937 issue, noting that "The Originator of Jazz and Swing" (in 1906 no less) was playing at The Jungle Inn. This was seen by a few fans, including another Down Beat writer, James Higgins, who followed the trail to U Street, "smack in the center of the town's jig district." Somebody else who found him at this time, likely through word of mouth, was Mabel. After some awkward apologies on Ferd's part concerning his seeming abandonment and lack of communication, she joined him for a time in Washington, which could have been a tenuous situation, but was handled in a civil matter by all parties. She made it clear that she was accepted as Morton's wife, and treated as such.

Down Beat continued to find interest in the historical aspect of the somewhat forgotten Jelly Roll Morton, and From December, 1938 to March, 1938, published a three-part article written by Professor Marshall Winslow Stearns, which outlined Morton's version of the history of jazz and swing. Having started out from the very opening with a falsehood - he gave his birth year as 1885, possibly to prove him as old enough to have invented jazz - it gave an accounting of a number of events of his earlier years; some true, some enhanced, and some later found to have never happened. To be fair, Stearns, perhaps a bit in awe of his subject, was partially complicit in the soft lies and blatant inaccuracies, having not expanded his research in many cases where it could have told another story.

The attention from Down Beat was followed by other stories, including one published in Washington, which credited him with the roar heard in Tiger Rag, taking his name from the composition which got him started (albeit in 1910), and having recorded for Victor as far back as 1905 (only 21 years off the mark). There were other fantastical tales within that March, 1938, article, including Morton ending up in jail at six months with a drunk baby-sitter, and referring to the area between New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, as the "Cradle of Swing," which is a suspect claim at best. However, Morton nonetheless represented jazz and American music history in a colorful manner, and his popularity was clearly gaining traction again, if among those interested in nostalgia or a window to the past. Even though he liked to talk about the past, he was also trying to promote his newer compositions and playing style, perhaps in an effort to become relevant to a new generation.

Even though he liked to talk about the past, he was also trying to promote his newer compositions and playing style, perhaps in an effort to become relevant to a new generation.

Even though he liked to talk about the past, he was also trying to promote his newer compositions and playing style, perhaps in an effort to become relevant to a new generation.

Even though he liked to talk about the past, he was also trying to promote his newer compositions and playing style, perhaps in an effort to become relevant to a new generation.Morton so believed many of the tales he had been spinning that he actually took umbrage at a radio broadcast he heard one evening that seemed to diminish his credit in jazz history. The March 25, 1938 broadcast of the popular syndicated radio show, Ripley's Believe It or Not, did a profile on W.C. Handy and a short history of jazz and blues. In that profile Handy was referred to as the originator of jazz and blues [a claim that has sense been disproven, as both came about by committee more so than any one individual]. Morton immediately fired off a letter that was closer to a manifesto than a simple challenge to the claim. Sent not only to Ripley's, but to the Baltimore Afro-American and Down Beat magazine, the latter who he felt had treated him favorably, the letter asked for Ripley's to furnish proof of their information, as he knew better. In fact, he had invented jazz in New Orleans in 1902, several years before Saint Louis Blues had been played in 1911 [it was actually 1915]. Having allegedly met Handy in 1908, Morton noted that he did not have nearly the ability required to play such music, and actually [a somewhat correct assertion] had taken many of his themes from other musicians, forming his own works. After going on about the supposedly true history of how Saint Louis Blues really became famous, which was through his own arrangement as played by white bandleader and self-proclaimed "King of Jazz" Paul Whiteman (also a spurious claim), he went on to explain how the standard arrangement of instruments for jazz bands evolved, and closed with a lament about the need for stricter copyright laws, no doubt a reference to his ongoing battle with Melrose Music. A similar letter found its way into an edited version in the Washington Post in early May. Before long they were a point of discussion in the music business, and in spite of Morton's wishing Handy success in the music business, it could not help but chill their relationship, as well as negatively taint the opinion of some readers who knew better against Morton and his attitude.

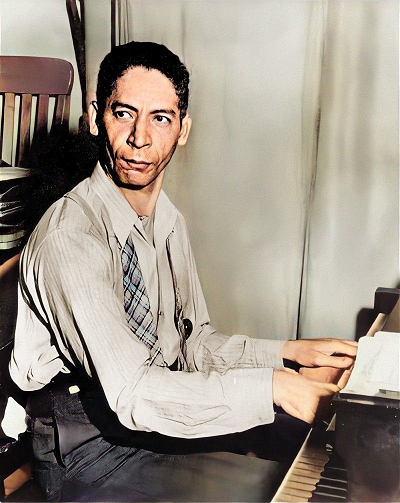

Either because of the Down Beat articles or the Ripley's melee, Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton was fortuitously "rediscovered" by historian Alan Lomax in May of 1938. Lomax was a Texas native who, like his father, John Avery Lomax, became a folk-music archivist. The Lomax ventures starting in 1933 were largely funded by the Library of Congress, and they essentially went out into the field around various parts of the country with recording equipment capturing what they felt was the most genuine or indigenous folk music from each locale. Some artists who later became well known were actually made so through the efforts of the Lomaxes, including folk singer Woody Guthrie and blues guitarist Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter. In 1937 at age 22, he became a Washington resident when the Library appointed him as an assistant archive director, essentially a custodian and historian for the work he and his father had already accomplished.

In 1937 at age 22, he became a Washington resident when the Library appointed him as an assistant archive director, essentially a custodian and historian for the work he and his father had already accomplished.

In 1937 at age 22, he became a Washington resident when the Library appointed him as an assistant archive director, essentially a custodian and historian for the work he and his father had already accomplished.

In 1937 at age 22, he became a Washington resident when the Library appointed him as an assistant archive director, essentially a custodian and historian for the work he and his father had already accomplished.It was Jelly Roll enthusiast and record collector Sidney Martin who actually introduced Morton to Lomax. This presented a unique opportunity for Lomax, because unlike many of his subjects, Ferd had already been well-recorded, even if his efforts were becoming distant memories. In this instance, it allowed Alan to focus more on the history of the music, including blues, ragtime and stomps, from the slightly inflated but still informed point of view of Morton. Having obtained permission and some funding, Alan took a Presto disk recorder (it seems likely that there were two in order to overlap the end of one disc with the start of another) to the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge auditorium, and between May 23 and December 14, 1938, recorded around nine hours of conversations with and music played by Morton. Some was biographical and some was historical in context, but in spite of some inaccuracies or selective memory moments on the part of Morton, it remains one of the first and best oral histories of the ragtime era and the days of early jazz.

The resulting recordings eventually begat three separate threads, two of which, when they first appeared, were groundbreaking, even if time has managed to add a number of annotations or corrections to each. The first was Lomax's book Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, which appeared in 1950 some nine years after Morton's death, and incidentally around the same time as another pioneering book that touched on Morton here and there, They All Played Ragtime by Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis. Alan, who was still in his mid-thirties when his tome was published, did the best he could with the information he had gotten a decade prior. There was some research outside of the sessions with Morton applied to the text, but much of it was riddled with inaccuracies, misalignments, or plain old misinformation, some of it coming from Morton, and some of it through the difficult process of listening to the discs which sometimes had noises or other errors. The latter problem was particularly prevalent when it came to how he interpreted the pronunciation and spelling of many of the names Morton ran off during his narrative. There have been some improved texts since that time, but one of the best sources to consider outside of Lomax's book is the research compiled at the site of the late Mike Meddings of England (see credits below for more), which although it is not as much a narrative like a book, could be considered a detailed annotation of Morton's life with a number of interesting sidebars. Without Lomax's accumulative efforts, the information we have now on Morton would be lacking to quite a degree.

which although it is not as much a narrative like a book, could be considered a detailed annotation of Morton's life with a number of interesting sidebars. Without Lomax's accumulative efforts, the information we have now on Morton would be lacking to quite a degree.

which although it is not as much a narrative like a book, could be considered a detailed annotation of Morton's life with a number of interesting sidebars. Without Lomax's accumulative efforts, the information we have now on Morton would be lacking to quite a degree.

which although it is not as much a narrative like a book, could be considered a detailed annotation of Morton's life with a number of interesting sidebars. Without Lomax's accumulative efforts, the information we have now on Morton would be lacking to quite a degree.The second thread involved the recorded material itself. There were many faults in the recordings, the most prevalent one being a lack of consistent speed. The Presto machine(s) had been adapted to work on batteries, but it would seem likely that AC power would have been used for the sessions, unless the reconfiguration of the device removed that capability. They also reportedly ran anywhere from 80 to 87 RPM, 85 being the best average speed to reproduce the content at the proper pitch. Still, the speed was not consistent between discs, and not even from the start to finish of a single disc. Even though they resided at Library of Congress, (and possibly a copy that ended up with Morton, and then his estate), permission was needed to release any of the material for the public. After several attempts by collectors and enthusiasts to gain access to them through his estate lawyer, a representative was sent by Circle Records, which was run by Rudi Blesh, to secure the permission to run off a limited edition. The plea worked, and Blesh spent time at the Library of Congress trying to get an acceptable transfer from their staff. The job was apparently rushed, and little or no effort was made to fix sound issues, and particularly speed issues, perhaps in order to move Blesh on his way.

Editing had to have been an issue, even when dealing with hard-core enthusiasts, because some of Morton's material was, itself, hard-core in its profanity and graphic content. With some effort, however, perhaps just over 300 sets of the dubs were released to the public through mail order in the late summer of 1947, which was in the form of 45 Vinylite 12" discs. It is notable that the following year would see the introduction of both the long-playing record and commercial audio tape recording, both of which would have been of great benefit to this particular project. Blesh did attempt to rectify some of the issues by presenting a release in 1950 consisting of 12 LPs, but all of the noise and speed faults remained, making it even a poorer seller than the first edition. Over the years, technology has been re-applied to the originals to fix noise and speed faults, resulting in a limited-scope 4 CD set release partially funded by Congress in 1994. Eventually the entire set of recordings, cleaned up, speed corrected, and with all of the original profanity and pornography intact, was released in 2005.

Over the years, technology has been re-applied to the originals to fix noise and speed faults, resulting in a limited-scope 4 CD set release partially funded by Congress in 1994. Eventually the entire set of recordings, cleaned up, speed corrected, and with all of the original profanity and pornography intact, was released in 2005.