Due to unfortunate circumstances associated with racial bias concerning some black figures of the ragtime era, sketchy record-keeping, and the commonality of his name, James White's known information outside of his music career is relatively sparse. He was born in Coffeeville, Alabama, in 1881 to Millie White and, given that he and his siblings, Nicie (8/1876) and Reuben (5/1879) were classified as Mulatto and their mother Black, a possibly white father whose identity remains unknown. The January 1 birth date from his World War I draft registration might be questioned as it was sometimes used as a placeholder when the registrant was not sure of their actual date of birth, but only their approximate age. The most likely entry for White in the 1900 census showed him to be a common laborer in Alabama. His mother had remarried in the early 1880s to William Dungan, and remained in Coffeeville through at least 1900. Whether James had anything other than a rudimentary music education is unclear, but many musicians of his ilk learned from hanging around with and even playing with established players, of which there were many in the South. It is clear that White had musical talent, which can sometimes rise above a lack of a formal musical education.

The most likely entry for White in the 1900 census showed him to be a common laborer in Alabama. His mother had remarried in the early 1880s to William Dungan, and remained in Coffeeville through at least 1900. Whether James had anything other than a rudimentary music education is unclear, but many musicians of his ilk learned from hanging around with and even playing with established players, of which there were many in the South. It is clear that White had musical talent, which can sometimes rise above a lack of a formal musical education.

The most likely entry for White in the 1900 census showed him to be a common laborer in Alabama. His mother had remarried in the early 1880s to William Dungan, and remained in Coffeeville through at least 1900. Whether James had anything other than a rudimentary music education is unclear, but many musicians of his ilk learned from hanging around with and even playing with established players, of which there were many in the South. It is clear that White had musical talent, which can sometimes rise above a lack of a formal musical education.

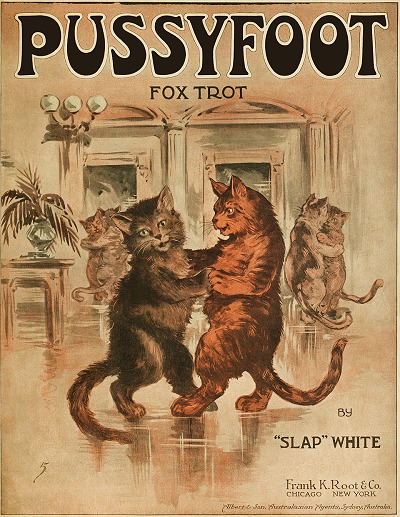

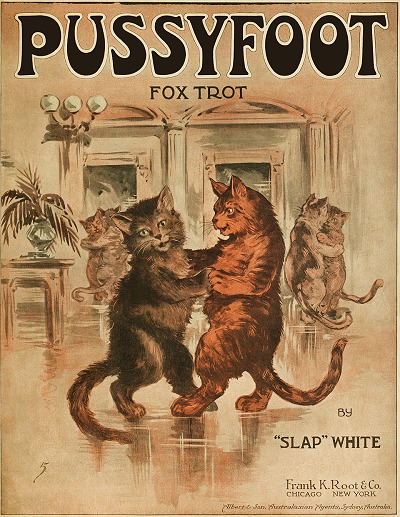

The most likely entry for White in the 1900 census showed him to be a common laborer in Alabama. His mother had remarried in the early 1880s to William Dungan, and remained in Coffeeville through at least 1900. Whether James had anything other than a rudimentary music education is unclear, but many musicians of his ilk learned from hanging around with and even playing with established players, of which there were many in the South. It is clear that White had musical talent, which can sometimes rise above a lack of a formal musical education.On January 7, 1904, James was married to Hattie Wilson in Hale County, Alabama. At some point soon after that, perhaps 1906 or 1907, the couple relocated to Chicago, Illinois, where White found work as a musician, primarily on the piano. The 1910 census taken in Chicago showed James and Hattie hosting two lodgers in their home, with James listed as a music writer. This may have been optimistic at this point, since he only had one known published piece in circulation, Howdy, Cy. However, his wishful thinking would soon come to fruition. In 1912, James composed a piece that rode on the coattails of the instantly popular Waiting for the Robert E. Lee by L. Wolfe Gilbert and Lewis F. Muir. I'm Goin' to Mobile on the Robert E. Lee was followed up by some of his first collaborations, songs written to lyrics by Chicago writer Billy Johnson. It is possible, based on passing mentions, that one of his more famous works, Pussyfoot a.k.a. The Pussyfoot Prance, was released as the instrumental Pussyfoot March in 1913. The piece, with that title, would be recorded a couple of times in the 1910s. Mentions of him playing on the South Side with his "colored entertainers" at venues like that of Roy Jones Café started to appear more frequently in 1912.

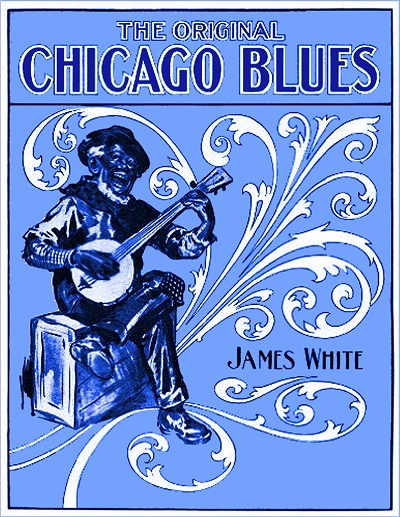

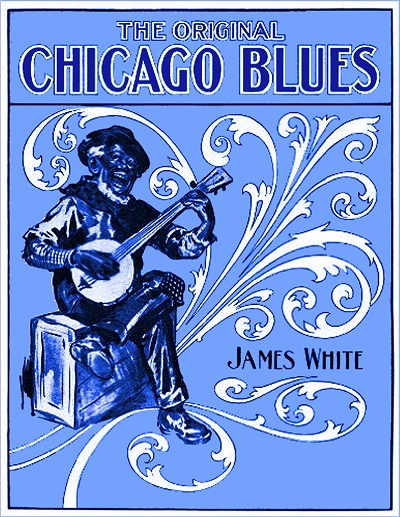

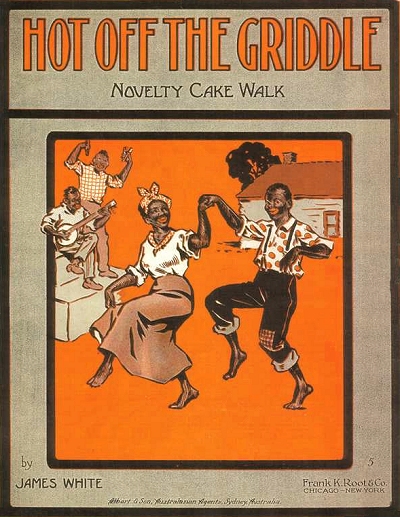

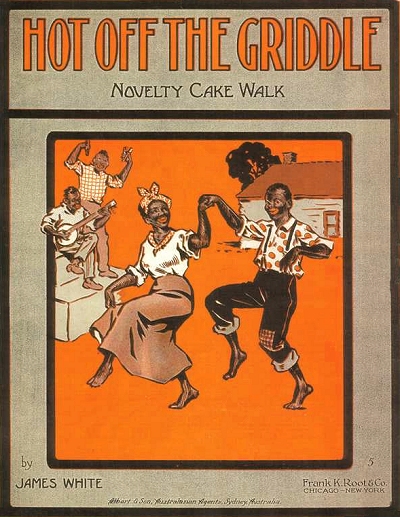

While White was not especially prolific (even though a couple of articles mentioned he had written over 400 pieces by 1917), he was actually relatively well-published over the next few years considering the difficulties that some black composers had getting their works into print. This included one of his Chicago peers, Shelton Brooks, who ran in the same circles as White. Some of his more vivacious works found their way to piano rolls and recordings, such as Hot off the Griddle and Neutrality Rag. However, his best-known work has been cited, perhaps a bit too generously, as having influenced a similar work by another composer. The Original Chicago Blues was copyrighted in April of 1915 by Frank Root, perhaps on the street as issued by McKinley Music even before that. Much later in the year, Will Rossiter, with whom James had also done some business, issued The Chicago Blues composed by Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. Within a month or two it was reissued under its more familiar title, The Original Jelly Roll Blues. The similarity between the pieces is vague at best, other than the title, which may have been a gaffe by Rossiter. Morton appears to have had little to do with the affair, as many musicians had their pieces named or renamed by publishers for a variety of reasons. He certainly can be acquitted of having plagiarized any of White's somewhat popular piece, given how distinct the construction of Jelly Roll Blues was. However, Rossiter's adding "original" to the title may have been an homage or veiled reference to the White work. Beyond that, White's Original Chicago Blues bears more of a similarity to the half-rag/half-blues numbers issued by W.C. Handy during that time period, such as Memphis Blues.

This included one of his Chicago peers, Shelton Brooks, who ran in the same circles as White. Some of his more vivacious works found their way to piano rolls and recordings, such as Hot off the Griddle and Neutrality Rag. However, his best-known work has been cited, perhaps a bit too generously, as having influenced a similar work by another composer. The Original Chicago Blues was copyrighted in April of 1915 by Frank Root, perhaps on the street as issued by McKinley Music even before that. Much later in the year, Will Rossiter, with whom James had also done some business, issued The Chicago Blues composed by Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. Within a month or two it was reissued under its more familiar title, The Original Jelly Roll Blues. The similarity between the pieces is vague at best, other than the title, which may have been a gaffe by Rossiter. Morton appears to have had little to do with the affair, as many musicians had their pieces named or renamed by publishers for a variety of reasons. He certainly can be acquitted of having plagiarized any of White's somewhat popular piece, given how distinct the construction of Jelly Roll Blues was. However, Rossiter's adding "original" to the title may have been an homage or veiled reference to the White work. Beyond that, White's Original Chicago Blues bears more of a similarity to the half-rag/half-blues numbers issued by W.C. Handy during that time period, such as Memphis Blues.

This included one of his Chicago peers, Shelton Brooks, who ran in the same circles as White. Some of his more vivacious works found their way to piano rolls and recordings, such as Hot off the Griddle and Neutrality Rag. However, his best-known work has been cited, perhaps a bit too generously, as having influenced a similar work by another composer. The Original Chicago Blues was copyrighted in April of 1915 by Frank Root, perhaps on the street as issued by McKinley Music even before that. Much later in the year, Will Rossiter, with whom James had also done some business, issued The Chicago Blues composed by Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. Within a month or two it was reissued under its more familiar title, The Original Jelly Roll Blues. The similarity between the pieces is vague at best, other than the title, which may have been a gaffe by Rossiter. Morton appears to have had little to do with the affair, as many musicians had their pieces named or renamed by publishers for a variety of reasons. He certainly can be acquitted of having plagiarized any of White's somewhat popular piece, given how distinct the construction of Jelly Roll Blues was. However, Rossiter's adding "original" to the title may have been an homage or veiled reference to the White work. Beyond that, White's Original Chicago Blues bears more of a similarity to the half-rag/half-blues numbers issued by W.C. Handy during that time period, such as Memphis Blues.

This included one of his Chicago peers, Shelton Brooks, who ran in the same circles as White. Some of his more vivacious works found their way to piano rolls and recordings, such as Hot off the Griddle and Neutrality Rag. However, his best-known work has been cited, perhaps a bit too generously, as having influenced a similar work by another composer. The Original Chicago Blues was copyrighted in April of 1915 by Frank Root, perhaps on the street as issued by McKinley Music even before that. Much later in the year, Will Rossiter, with whom James had also done some business, issued The Chicago Blues composed by Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton. Within a month or two it was reissued under its more familiar title, The Original Jelly Roll Blues. The similarity between the pieces is vague at best, other than the title, which may have been a gaffe by Rossiter. Morton appears to have had little to do with the affair, as many musicians had their pieces named or renamed by publishers for a variety of reasons. He certainly can be acquitted of having plagiarized any of White's somewhat popular piece, given how distinct the construction of Jelly Roll Blues was. However, Rossiter's adding "original" to the title may have been an homage or veiled reference to the White work. Beyond that, White's Original Chicago Blues bears more of a similarity to the half-rag/half-blues numbers issued by W.C. Handy during that time period, such as Memphis Blues.In terms of output, 1915 was one of White's best years, in part because of a brief partnership with composer Jack Frost, who also was known for his music, although Frost's contributions to White's compositions were entirely lyrical. Other than Neutrality Rag, which was a reference to the then popular stance of the United States' minimal involvement with the ongoing war in Europe, none were really hits of any stature outside of Chicago. In 1916, Frost added lyrics to White's clever march, which had been released that year as an instrumental fox trot, and now as the song titled Pussyfoot Prance. The cuteness of the cover probably had as much to do with its popularity as the piece itself, and many extant copies of both the song and instrumental can still be found in antique malls and sheet music collections a century later.

Other than Neutrality Rag, which was a reference to the then popular stance of the United States' minimal involvement with the ongoing war in Europe, none were really hits of any stature outside of Chicago. In 1916, Frost added lyrics to White's clever march, which had been released that year as an instrumental fox trot, and now as the song titled Pussyfoot Prance. The cuteness of the cover probably had as much to do with its popularity as the piece itself, and many extant copies of both the song and instrumental can still be found in antique malls and sheet music collections a century later.

Other than Neutrality Rag, which was a reference to the then popular stance of the United States' minimal involvement with the ongoing war in Europe, none were really hits of any stature outside of Chicago. In 1916, Frost added lyrics to White's clever march, which had been released that year as an instrumental fox trot, and now as the song titled Pussyfoot Prance. The cuteness of the cover probably had as much to do with its popularity as the piece itself, and many extant copies of both the song and instrumental can still be found in antique malls and sheet music collections a century later.

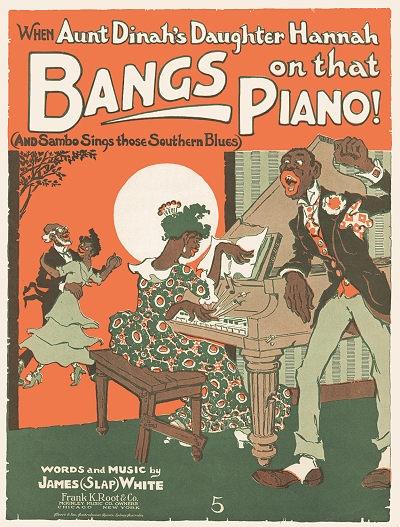

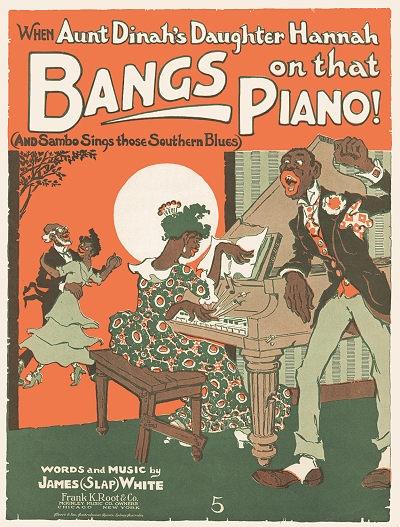

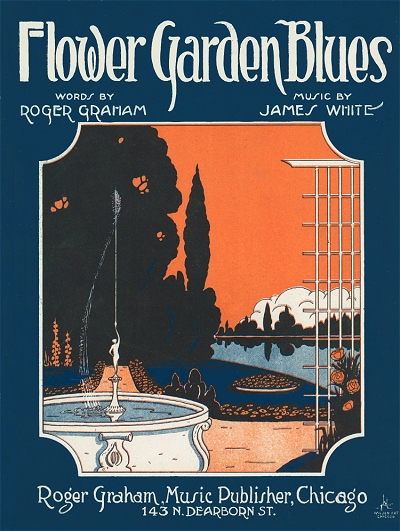

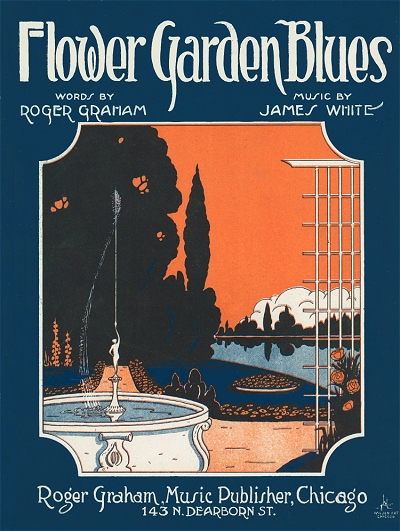

Other than Neutrality Rag, which was a reference to the then popular stance of the United States' minimal involvement with the ongoing war in Europe, none were really hits of any stature outside of Chicago. In 1916, Frost added lyrics to White's clever march, which had been released that year as an instrumental fox trot, and now as the song titled Pussyfoot Prance. The cuteness of the cover probably had as much to do with its popularity as the piece itself, and many extant copies of both the song and instrumental can still be found in antique malls and sheet music collections a century later.Having been largely associated in his earlier years with publishers Will Rossiter and Frank Root, around 1915 White became involved with Roger Graham, who was both a publisher and a lyric writer and sometime composer. In fact, Graham referred to his new compatriot as "a colored Irving Berlin," as quoted in the New York Clipper of August 28, 1915. Along with lyricist Walter Hirsch, at a time when jazz was overtaking the music world in 1918, White and Graham concocted Jazz Band Blues, which quickly became a hit in Chicago and well beyond, finding its way to a few recorded versions. It also helped to spread a new nickname for James that he had been using since 1915, that of "Slap." The origin is unclear, but the version that can be perhaps discounted has to do with the Six Brown Brothers saxophone recordings of three of his pieces. Some historians have alleged that James played as one of the Brown Brothers on their recordings, and that it was his version of a rhythmic tongue slap on those pieces that gave them an extra edge on their unique sound, giving him the "Slap" moniker. However, there is plenty of contradictory data, including geography (many of the records in question were recorded in Camden, New Jersy), the fact that the Brown Brothers were all white, and James' skill set being primarily on the piano, that should perhaps put that conjecture to rest, as White was never directly cited by any credible source of that time as having been part of the group. However he got the unusual title, which may have had something to do with pianistic technique, many of his pieces from 1915 to 1920 were credited to James "Slap" White, and a couple of even earlier references back to 1912 used "Slap Rags" as a descriptive. He was frequently mentioned as "Professor Beethoven" or "Professor Slap" as well in the press. Such nicknames became quite popular during the early part of the jazz era. As of early 1917 James and his "jass band" were performing at various veneus in the Midwest, including a residency at The Empress in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in December 1916, and at The Park Hotel in Madison, Wisconsin, as advertised in mid-January of that year.

as White was never directly cited by any credible source of that time as having been part of the group. However he got the unusual title, which may have had something to do with pianistic technique, many of his pieces from 1915 to 1920 were credited to James "Slap" White, and a couple of even earlier references back to 1912 used "Slap Rags" as a descriptive. He was frequently mentioned as "Professor Beethoven" or "Professor Slap" as well in the press. Such nicknames became quite popular during the early part of the jazz era. As of early 1917 James and his "jass band" were performing at various veneus in the Midwest, including a residency at The Empress in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in December 1916, and at The Park Hotel in Madison, Wisconsin, as advertised in mid-January of that year.

as White was never directly cited by any credible source of that time as having been part of the group. However he got the unusual title, which may have had something to do with pianistic technique, many of his pieces from 1915 to 1920 were credited to James "Slap" White, and a couple of even earlier references back to 1912 used "Slap Rags" as a descriptive. He was frequently mentioned as "Professor Beethoven" or "Professor Slap" as well in the press. Such nicknames became quite popular during the early part of the jazz era. As of early 1917 James and his "jass band" were performing at various veneus in the Midwest, including a residency at The Empress in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in December 1916, and at The Park Hotel in Madison, Wisconsin, as advertised in mid-January of that year.

as White was never directly cited by any credible source of that time as having been part of the group. However he got the unusual title, which may have had something to do with pianistic technique, many of his pieces from 1915 to 1920 were credited to James "Slap" White, and a couple of even earlier references back to 1912 used "Slap Rags" as a descriptive. He was frequently mentioned as "Professor Beethoven" or "Professor Slap" as well in the press. Such nicknames became quite popular during the early part of the jazz era. As of early 1917 James and his "jass band" were performing at various veneus in the Midwest, including a residency at The Empress in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in December 1916, and at The Park Hotel in Madison, Wisconsin, as advertised in mid-January of that year.In 1917, as part of a famous court case that ended up being case law for the music business for some time, James was a key witness for Graham in a lawsuit filed by New York publisher Leo Feist and Original Dixieland Jazz Band manager Max Hart (Hart Vs. Graham). At the center of this was whether Graham could publish a piece by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band written collectively (they claimed separately) by founders Nick LaRocca, Larry Shields and Alcide Nuniez, namely, the Livery Stable Blues. In essence, it was a renamed variation on their previously recorded Barnyard Blues which had been issued by Feist earlier in the year. The battle was more between the publishers than the composers. Among those called to testify for either side and also to form a jazz ensemble to play the two pieces in question were composer Ernie Erdman, drummer Johnnie Stein, band leader Tom Brown, Schiller Café proprietor Sam Hare, and Professor Slap White. It was White who provided the pivotal testimony that decided the case, good or bad, as noted in the Chicago Times of October 12, 1917, and the Music Trade Review of October 20:

… One of the bright spots in the case was the bringing out of the fact that one of the witnesses known as Prof. Beethoven (alias Slap) White, a black man, had composed blues for Brown's Band, which played in a red cafe, in New Orleans.

In the complaint it was alleged that "The Barnyard Blues" enjoyed priority of copyright over "The Livery Stable Blues," and that the latter was, therefore, an infringement of the first piece, owing to alleged similarity of melody and certain barnyard calls. …

Prof. White gummed up the trial by stating that all blues were alike.

"Well, what are blues?" he was asked.

"Blues are blues," was the reply.

"Are there no differences between the various blues?"

"Well, they might be, but, on the other hand, all blues are the same. Take Alligator Blues and Ostrich Walk Blues. They're different, but they're both blues and all blues are blues."

The attorney sadly dismissed the witness.

The final outcome was that the court, the attorneys and the witnesses gave up attempts to fathom the matter, and the case was dismissed for want of equity. Both song numbers may remain on the market, and both composers may draw royalties …

Late in 1917, White, along with W.R. Williams, composed Good Bye My Chocolate Soldier Boy, an homage to black soldiers departing for the European conflict, creating another minor hit that warranted at least a couple of large printings. On his draft record, completed in 1918, James noted his point of contact as his sister, Nicie, living at that time in Birmingham, Alabama, where she had relocated around 1911. His listed occupation was, not surprisingly, musician and composer. The growing popularity of Chicago Jazz and black composers in that field was not lost on an editor at the New York Clipper, who included this tidbit in the March 25, 1919 edition:

The growing popularity of Chicago Jazz and black composers in that field was not lost on an editor at the New York Clipper, who included this tidbit in the March 25, 1919 edition:

The growing popularity of Chicago Jazz and black composers in that field was not lost on an editor at the New York Clipper, who included this tidbit in the March 25, 1919 edition:

The growing popularity of Chicago Jazz and black composers in that field was not lost on an editor at the New York Clipper, who included this tidbit in the March 25, 1919 edition:The little song writing money that is "hanging around loose" in Chicago seems to be going into the coffers of colored writers. Many of the boys from lower State Street are flashing diamonds given them, as tokens of appreciation, by publishers who found their output profitable. Will Rossiter has always taken great interest in the compositions of Shelton Brooks, and William McKinley has reaped a harvest on Clarence Jones' ideas. Both these Western publishers are taking numbers from James (Slap) White almost as quickly as he completes them, while Spencer Williams has crept into many local catalogues.

Another point of confusion concerning White which surfaced later in 1919 was one of coincidence and happenstance, but also required a bit of sorting out. The Music Trade Review of December 6, 1919, reported that:

James S. White Co., Inc., Boston, Mass., have appointed James Altiere their Chicago representative. Mr. Altiere is located in the Randolph building, 145 North Clark street, where he will look after the professional work and handle the James S. White Co.'s catalog, laying particular stress on the following numbers: "Hot Coffee," featured by Wilbur Sweatman's jazz band; "Oh Danny, Love Your Annie," and "My Pretty Little China Maid," featured by Libonati the Great, and 100 other vaudeville acts.

"My Pretty Little China Maid" is by James (Slap) White, who has written numbers of hits for the McKinley Co., and Will Rossiter.

As it turns out, James Simeon White was indeed a black Boston musician and briefly publisher whose company happened to issue the work by James M. White, and not the Chicago James White relocated to the East Coast. Given that "Slap" White's draft record had been filled out by what appears to be a left-handed female, his literary skills were potentially minimal at best, so it is somewhat unlikely he would have run a music publishing company, especially in an unfamiliar environment, as Boston would have been to him at that time. His association was through co-composer Altiere, who had moved to Chicago for the publisher to manage composing talent in the Windy City for his short-lived firm.

Given that "Slap" White's draft record had been filled out by what appears to be a left-handed female, his literary skills were potentially minimal at best, so it is somewhat unlikely he would have run a music publishing company, especially in an unfamiliar environment, as Boston would have been to him at that time. His association was through co-composer Altiere, who had moved to Chicago for the publisher to manage composing talent in the Windy City for his short-lived firm.

Given that "Slap" White's draft record had been filled out by what appears to be a left-handed female, his literary skills were potentially minimal at best, so it is somewhat unlikely he would have run a music publishing company, especially in an unfamiliar environment, as Boston would have been to him at that time. His association was through co-composer Altiere, who had moved to Chicago for the publisher to manage composing talent in the Windy City for his short-lived firm.

Given that "Slap" White's draft record had been filled out by what appears to be a left-handed female, his literary skills were potentially minimal at best, so it is somewhat unlikely he would have run a music publishing company, especially in an unfamiliar environment, as Boston would have been to him at that time. His association was through co-composer Altiere, who had moved to Chicago for the publisher to manage composing talent in the Windy City for his short-lived firm.There was no reliable sighting of White in the January, 1920, Federal census, nor in Chicago directories or newspapers. He evidently was not in favor of the Volstead Act that enforced the national prohibition of alcohol from 1920 to 1933, and like many of his peers simply left the country. In this case, it was not to Europe, but rather to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The 1921 census taken in Montreal, specifically in the suburb of St Joseph, showed that White had also remarried to a somewhat older woman named Irene, and that he was working as a musician. There are scant mentions of him in Montreal newspapers during the early-to-mid-1920s. However, according to a mention in the Chicago Defender of December 31, 1927, White had returned and would celebrate the New Year in his new home New York City. There is one composition attributed to him in 1928 with his peer Clarence Williams, indicating he may still have been part of the Chicago musical scene, even from Manhattan, although it may also have been composed earlier and just issued that year.

Beyond this, the trail grows cold. It may be surmised either that James died during the 1930s (his sister Nicie had passed on before the 1930 enumeration), or that he was simply not counted among the many who became homeless and destitute during the early part of the Great Depression. There were a number of James Whites that were deceased in both Chicago and New York between 1930 and 1935, but there were not enough specifics on the records to pinpoint the musician. White left behind an admirable pre-jazz musical legacy, given his hardscrabble beginnings and the struggles faced by many black artists of the period.

Thanks go to researcher Reginald Pitts who found some clues on where White had disappeared after 1920, leading the author to some of the additional information, and helping to confirm that the identity of Boston publisher James Simeon White was distinct from James "Slap" White.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions