|

Arthur Owen Marshall (November 20, 1881 to August 18, 1968) | |

Known Published Compositions Known Published Compositions | |

|

1900

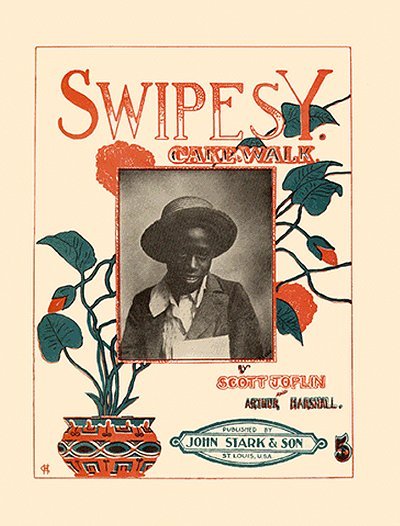

Swipesy Cakewalk [1]1906

Kinklets1907

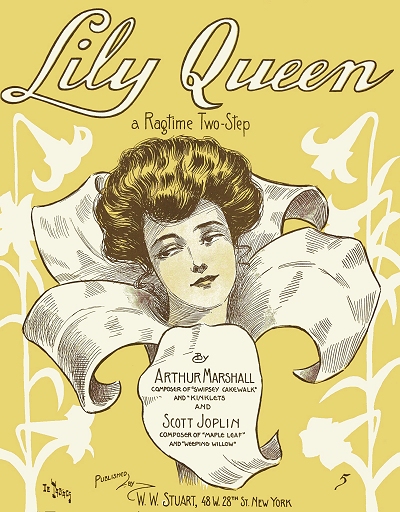

Lily Queen [1]Missouri Romp (c.1907) 1908

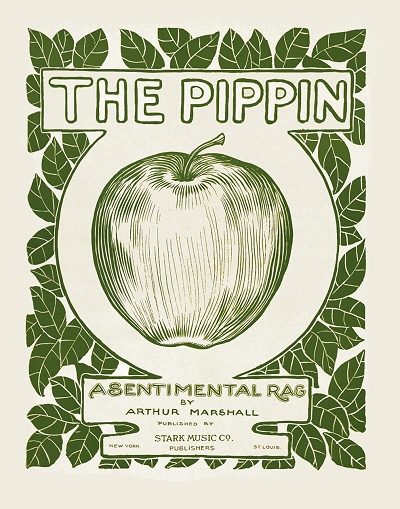

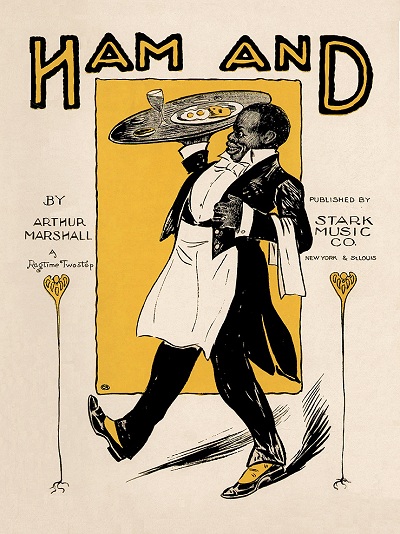

Ham And!The Peach: A Sentimental Rag The Glory of the Cubs [w/F.R. Sweirgen] The Pippin Rag 1949

Silver Arrow Rag |

1950

National Prize Ragc.1966

Century PrizeSilver Rocket 1974 (Posth)

I'll Wait Until My Dream Girl ComesAgain 1976 (Posth)

Little Jack's Rag1980 (Posth)

The Miracle of a Birth

1. w/Scott Joplin (?)

|

Arthur Marshall grew up in the same environment as another future collaborator with Scott Joplin, Scott Hayden. Yet his story is quite different from that of his Lincoln High School classmate. Many sources claim that he was born on a farm in Saline County, Missouri. However, the Marshalls were living in Pettis County, Missouri, near the future location of Sedalia, for the 1880 census. While it is possible that they migrated north over the next several months, it still puts the county of birth for Arthur into question. The 1900 census shows an 1880 birth date, his 1917 draft card 1882, and later census records point to 1883. However, 1881 is most commonly accepted and is likely more accurate than the later dates. It also appears on his death certificate and Social Security record. According to the 1900 census he was one of three surviving children out of a sobering total of fourteen born to woodcarver Edward Marshall and his bride Emily Rector, the others apparently having died at birth, or at least in infancy. Two other surviving siblings included Martha "Mattie" Ella (1867) and Samuel Lee W. (1877)

When Arthur was still very young, the Marshalls moved into the new town Sedalia, in part because of better public education opportunities that were afforded the growing black population of that city. While there he attended the segregated Lincoln High School, where at least a couple of teachers gave nominal instruction in music. The family was relatively poor, and Arthur had to help work make ends meet while attending school. He was shown as a porter in a Sedalia barber shop in the 1900 enumeration, possibly working as a shoe shiner. His mother Emily Marshall was a washerwoman, and his illiterate father Edward Marshall, now 60, had no discernible career, yet they did own their home, so he may have done well during his years as a wood craftsman.

possibly working as a shoe shiner. His mother Emily Marshall was a washerwoman, and his illiterate father Edward Marshall, now 60, had no discernible career, yet they did own their home, so he may have done well during his years as a wood craftsman.

possibly working as a shoe shiner. His mother Emily Marshall was a washerwoman, and his illiterate father Edward Marshall, now 60, had no discernible career, yet they did own their home, so he may have done well during his years as a wood craftsman.

possibly working as a shoe shiner. His mother Emily Marshall was a washerwoman, and his illiterate father Edward Marshall, now 60, had no discernible career, yet they did own their home, so he may have done well during his years as a wood craftsman.When Joplin first arrived in Sedalia, Missouri, he sought lodging with the Marshall family. Arthur had already taken some private lessons in classical music years before, and was versed with piano technique and a gift for syncopation. Joplin collaborated with his new protégé on Swipesy Cakewalk, the only rag with Joplin's name on it published in 1900. Joplin also helped get the young pianist a job at the now-famous Maple Leaf Club during its single year of existence in 1899. It was there that Marshall reportedly got into a fight on October 1, 1899, with one Ernst Edwards over a woman. The fight was taken downstairs from the club onto Main Street where Marshall allegedly beat Edwards with a cane, the latter responding with a drawn gun. Marshall left the scene at that point, ending the altercation.

Joplin encouraged Arthur to enroll in the George R. Smith College in Sedalia where he had attended in pursuit of a music degree. Marshall went even further than his mentor had, gaining experience in music theory, and eventually graduating from the Teacher's Institute with a teaching license. Whether Arthur actually pursued a career in teaching is unclear, but he did have a good career as a performer.

Marshall had worked his way through school playing ragtime in public venues and for dances and special occasions. He also went where the work was, in the brothels, where substantial tips regularly exceeded his standard pay by a great deal. While still in college, he joined McCabe's Minstrels playing for intermissions for nearly two years. He also spent some time in Saint Louis living with Joplin and Hayden for a short period. In 1903, prior to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis, Marshall came once again to the growing city and joined with Scott Hayden in Joplin's short-lived Drama Company, which briefly toured Joplin's opera A Guest of Honor. At least two mentions in contemporary papers list either a Latisha or Letitia Marshall, one of a Mrs. Arthur Marshall, and another of a Letitia Howell, which points to the possibility that Marshall was briefly married, or even posing as married to this cast member. If this is a fact, they were not wed for very long. After the tour folded in the autumn of 1903, Marshall became a fixture in Tom Turpin's Rosebud Saloon as well.

In 1903, prior to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis, Marshall came once again to the growing city and joined with Scott Hayden in Joplin's short-lived Drama Company, which briefly toured Joplin's opera A Guest of Honor. At least two mentions in contemporary papers list either a Latisha or Letitia Marshall, one of a Mrs. Arthur Marshall, and another of a Letitia Howell, which points to the possibility that Marshall was briefly married, or even posing as married to this cast member. If this is a fact, they were not wed for very long. After the tour folded in the autumn of 1903, Marshall became a fixture in Tom Turpin's Rosebud Saloon as well.

In 1903, prior to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis, Marshall came once again to the growing city and joined with Scott Hayden in Joplin's short-lived Drama Company, which briefly toured Joplin's opera A Guest of Honor. At least two mentions in contemporary papers list either a Latisha or Letitia Marshall, one of a Mrs. Arthur Marshall, and another of a Letitia Howell, which points to the possibility that Marshall was briefly married, or even posing as married to this cast member. If this is a fact, they were not wed for very long. After the tour folded in the autumn of 1903, Marshall became a fixture in Tom Turpin's Rosebud Saloon as well.

In 1903, prior to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis, Marshall came once again to the growing city and joined with Scott Hayden in Joplin's short-lived Drama Company, which briefly toured Joplin's opera A Guest of Honor. At least two mentions in contemporary papers list either a Latisha or Letitia Marshall, one of a Mrs. Arthur Marshall, and another of a Letitia Howell, which points to the possibility that Marshall was briefly married, or even posing as married to this cast member. If this is a fact, they were not wed for very long. After the tour folded in the autumn of 1903, Marshall became a fixture in Tom Turpin's Rosebud Saloon as well.It was in Saint Louis that Arthur married Maude McMannes, possibly his second of four wives. During the 1904 Exposition, and frequently for years after in Saint Louis, there were wicked cutting contest where pianists would try to outplay each other, mostly in a friendly fashion. One of the best ways to get the upper hand was to have good material that the other pianist did not know, which as Marshall said, "caused them to write some pretty good rags." His reputation as both composer and pianist grew as a result of such contests. He apparently made more money for his playing than he did for his compositions. Having worked with publisher John Stark as Joplin had for his own Maple Leaf Rag, Arthur managed to get a nominal royalty deal and $50 payment from Stark on three of his solo works; Kinklets, Ham And!, and The Peach. However, when it came to negotiating with Stark on The Pippin, the publisher, or possibly his son Will, was less amenable to such a deal, and Marshall had to accept an outright payment of $10 and 200 copies of the published work.

In 1907, possibly due to an arrangement through Joplin, who was now in New York City, Lily Queen was published by W.W. Stuart in that city. Although it is credited to Joplin and Marshall, in later years Arthur insisted that he needed no extra help from his former mentor when writing the piece. So Joplin's name may have been a matter of marketing with a known quantity (Maple Leaf Rag is clearly mentioned on the cover), or there is the possibility that Joplin arranged it. It may also have been a method of getting further royalties for Arthur.

Although it is credited to Joplin and Marshall, in later years Arthur insisted that he needed no extra help from his former mentor when writing the piece. So Joplin's name may have been a matter of marketing with a known quantity (Maple Leaf Rag is clearly mentioned on the cover), or there is the possibility that Joplin arranged it. It may also have been a method of getting further royalties for Arthur.

Although it is credited to Joplin and Marshall, in later years Arthur insisted that he needed no extra help from his former mentor when writing the piece. So Joplin's name may have been a matter of marketing with a known quantity (Maple Leaf Rag is clearly mentioned on the cover), or there is the possibility that Joplin arranged it. It may also have been a method of getting further royalties for Arthur.

Although it is credited to Joplin and Marshall, in later years Arthur insisted that he needed no extra help from his former mentor when writing the piece. So Joplin's name may have been a matter of marketing with a known quantity (Maple Leaf Rag is clearly mentioned on the cover), or there is the possibility that Joplin arranged it. It may also have been a method of getting further royalties for Arthur.In 1906, Arthur and Maude were divorced, and he left Saint Louis, Marshall ventured to Chicago in 1906 where many of his colleagues had gone before him to seek new opportunities. There he met and married Julia Jackson in 1907, with whom he reportedly had three children, two girls and one boy, of which only Mildred Price (4/29/1908) survived. When Chicago did not turn up the wealth of work he had hoped for, Marshall moved back first to Sedalia then to Saint Louis in 1910. He was shown living again with his mother, his older brother and sister-in-law, and his wife Julia in Sedalia in April 1910, while working as barber and engaged in "odd jobs." Curiously, Julia showed as having had one child by that time, but there was no indication of Mildred in the household. Back in Saint Louis later that year Arthur entered one of the major contests at the Booker T. Washington Theatre run by the Turpin family. Marshall won the top prize ($5.00) and went to work at the Eureka, and later the Moonshine Gardens.

Julia died in childbirth from a placenta previa incident in Sedalia on June 18, 1915, leaving Arthur a widower. He returned to Saint Louis for at least another two years. Mildred went to live with his widowed sister Mattie Buford in Saint Louis (shown as Ella Buford) in the 1920 census. Arthur was shown on his 1917 draft record as a waiter at the Buckingham Hotel, and listed his mother, Emily, as still living in the area as well. Marshall then moved to Kansas City late in the year and retired from playing and composing. On November 25, 1919, Arthur got married one last time. His new bride was Kansas City native Odell Dillard Childs who had herself been widowed a few years prior. His age of 37 on the marriage certificate suggests an 1882 birth year. The couple was shown residing in Kansas City in 1920 with Arthur working in a packing house, and again in 1930 where he was now listed working at odd jobs, with Odell as a laundress in a private home, which was her family's profession before the couple was married. In both instances he shows his birth date as 1884, perhaps having either denied or simply forgotten his real age. Odell's age had also been deflated by two years. One decade later in 1940, they were living in the same home on White Avenue, with Arthur working as a W.P.A. laborer, and Odell still as a laundress. She would show the same occupation in 1950 in Kansas City, but Arthur would show none. Odell would die of hypertensive heart disease in Kansas City on July 4, 1954.

Mildred went to live with his widowed sister Mattie Buford in Saint Louis (shown as Ella Buford) in the 1920 census. Arthur was shown on his 1917 draft record as a waiter at the Buckingham Hotel, and listed his mother, Emily, as still living in the area as well. Marshall then moved to Kansas City late in the year and retired from playing and composing. On November 25, 1919, Arthur got married one last time. His new bride was Kansas City native Odell Dillard Childs who had herself been widowed a few years prior. His age of 37 on the marriage certificate suggests an 1882 birth year. The couple was shown residing in Kansas City in 1920 with Arthur working in a packing house, and again in 1930 where he was now listed working at odd jobs, with Odell as a laundress in a private home, which was her family's profession before the couple was married. In both instances he shows his birth date as 1884, perhaps having either denied or simply forgotten his real age. Odell's age had also been deflated by two years. One decade later in 1940, they were living in the same home on White Avenue, with Arthur working as a W.P.A. laborer, and Odell still as a laundress. She would show the same occupation in 1950 in Kansas City, but Arthur would show none. Odell would die of hypertensive heart disease in Kansas City on July 4, 1954.

Mildred went to live with his widowed sister Mattie Buford in Saint Louis (shown as Ella Buford) in the 1920 census. Arthur was shown on his 1917 draft record as a waiter at the Buckingham Hotel, and listed his mother, Emily, as still living in the area as well. Marshall then moved to Kansas City late in the year and retired from playing and composing. On November 25, 1919, Arthur got married one last time. His new bride was Kansas City native Odell Dillard Childs who had herself been widowed a few years prior. His age of 37 on the marriage certificate suggests an 1882 birth year. The couple was shown residing in Kansas City in 1920 with Arthur working in a packing house, and again in 1930 where he was now listed working at odd jobs, with Odell as a laundress in a private home, which was her family's profession before the couple was married. In both instances he shows his birth date as 1884, perhaps having either denied or simply forgotten his real age. Odell's age had also been deflated by two years. One decade later in 1940, they were living in the same home on White Avenue, with Arthur working as a W.P.A. laborer, and Odell still as a laundress. She would show the same occupation in 1950 in Kansas City, but Arthur would show none. Odell would die of hypertensive heart disease in Kansas City on July 4, 1954.

Mildred went to live with his widowed sister Mattie Buford in Saint Louis (shown as Ella Buford) in the 1920 census. Arthur was shown on his 1917 draft record as a waiter at the Buckingham Hotel, and listed his mother, Emily, as still living in the area as well. Marshall then moved to Kansas City late in the year and retired from playing and composing. On November 25, 1919, Arthur got married one last time. His new bride was Kansas City native Odell Dillard Childs who had herself been widowed a few years prior. His age of 37 on the marriage certificate suggests an 1882 birth year. The couple was shown residing in Kansas City in 1920 with Arthur working in a packing house, and again in 1930 where he was now listed working at odd jobs, with Odell as a laundress in a private home, which was her family's profession before the couple was married. In both instances he shows his birth date as 1884, perhaps having either denied or simply forgotten his real age. Odell's age had also been deflated by two years. One decade later in 1940, they were living in the same home on White Avenue, with Arthur working as a W.P.A. laborer, and Odell still as a laundress. She would show the same occupation in 1950 in Kansas City, but Arthur would show none. Odell would die of hypertensive heart disease in Kansas City on July 4, 1954.Arthur saw some hint of fame again after the first ragtime history book, They All Played Ragtime, was published in 1950. His increased exposure came particularly through the efforts of "Ragtime Bob" Darch who put Marshall out in front of the public again as a performer. Three of his last six compositions were printed in the third and fourth editions of They All Played Ragtime. He also had great opportunity to perform at the first few ragtime gatherings held over the next 18 years, most of them hosted by Darch. It was at one of those in 1959 that he played The Pea Picker, one of the only performances of that piece captured on a tape made by Trebor Tichenor. It may have been improvised or recently constructed, and is not a complete rag, but was resurrected in 2008 by the young historian and brilliant player Adam Swanson. Arthur Marshall died in Kansas City at 87 in 1968. He was buried at the Woodlawn Cemetery in nearby Independence, Missouri, but his grave remained unmarked for several years. In 1980, a local group that would become the Kansas City Ragtime Revelry managed to place a marker at his gravesite. Even into the 21st century through many performances of the ever-popular Swipesy and his other fine works, the spirit of Marshall still clearly inhabits ragtime.

Acknowledgement needs to be extended to Klaus and Hans Pehl, German researchers, who uncovered the information about Letitia/Latisha Marshall, and Dr. Ed Berlin for kindly conveying that information to the ragtime community. Also, Steve Hoog, who contributed the information on Marshall's grave in Independence, Missouri.