Scott Joplin (October ??, 1867(?) to April 1, 1917) | |

Ragtime Compositions (Known © and Comp. Years) Ragtime Compositions (Known © and Comp. Years) | |

|

1896

The Crush Collision March (a.k.a.The Great Crush Collision) Combination March Harmony Club Waltz 1899

Original RagsMaple Leaf Rag 1900

Swipsey Cake Walk [1]1901

Sunflower Slow Drag (1899) [2]The Augustan Club Waltz (1900) Peacherine Rag The Easy Winners 1902

CleophaThe Strenuous Life A Breeze From Alabama Elite Syncopations The Entertainer The Ragtime Dance (Song) (1899) March Majestic 1903

Something Doing [2]Weeping Willow Palm Leaf Rag 1904

The FavoriteThe Sycamore The Chrysanthemum The Cascades 1905

BethenaBinks' Waltz Leola The Rose-bud March 1906

EugeniaAntoinette The Ragtime Dance (Rag) |

1907

(The) NonpareilSearchlight Rag Gladiolus Rag Lily Queen [1] Rose Leaf Rag Heliotrope Bouquet [3] 1908

School of RagtimeFig Leaf Rag Sugar Cane Pine Apple Rag 1909

Wall Street RagSolace - A Mexican Serenade Pleasant Moments Country Club Euphonic Sounds Paragon Rag 1910

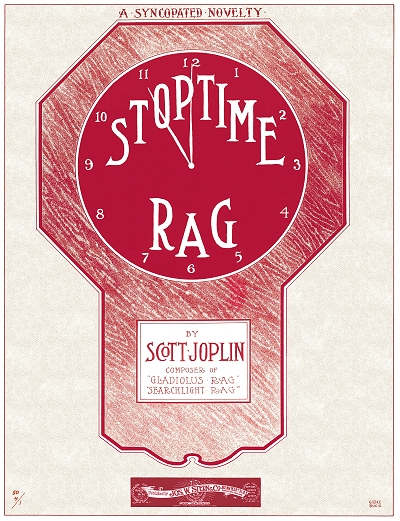

Stoptime Rag1911

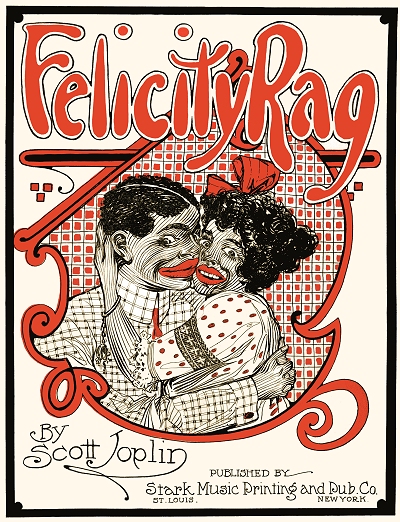

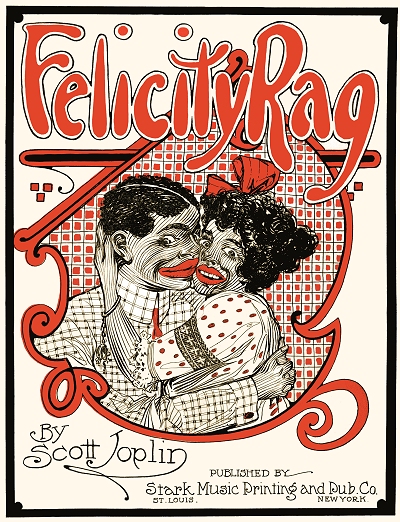

Felicity Rag [2]1912

Scott Joplin's New Rag1913

Kismet Rag [2]Treemonisha: Prelude to Act 3 A Real Slow Drag 1914

Magnetic Rag1915

Treemonisha: Frolic of the Bears1917 (Posth)

Reflection Rag (c.1908)1970 (Posth)

Silver Swan Rag (c.1914)

1. w/Arthur Marshall

2. w/Scott Hayden 3. w/Louis Chauvin |

Songs Songs | |

|

1895

Please Say You WillA Picture of Her Face 1902

I Am Thinking of My Pickaninny Days [4]1903

Little Black Baby [5]1904

Maple Leaf Rag Song (1903) [6]1905

Sarah Dear [4]1906

Good Bye Old Gal, Good Bye [7,8,13]1907

Snoring Sampson [9,13]When Your Hair is Like the Snow [10] |

1910

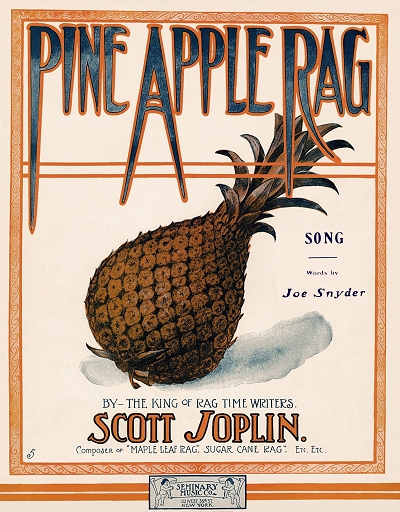

Pine Apple Rag Song [11]1911

Lovin' Babe [12,13]

4. w/Henry Jackson

5. w/Louise Armstrong Bristol 6. w/Sydney Brown 7. w/Mac Darden 8. w/H. Carroll Taylor 9. w/Harry La Mertha 10. w/Frederick Forrest Berry as Owen Spendthrift 11. w/Joe Snyder 12. w/Al. R. Turner 13. arr. by Scott Joplin |

Known Lost Works Known Lost Works | |

|

1901

A Blizzard1903

A Guest of Honor: OperaDude's Parade Patriotic Patrol Song/Inst based on Antoinette 1905

You Stand Good With Me, Babe |

c.1915?

Morning GloriesFor the Sake of All Syncopated Jamboree (Stage Presentation) Pretty Pansy Rag Recitative Rag c.1916?

If (Musical Comedy)Symphony No. 1 Piano Concerto |

Rollography Rollography | |

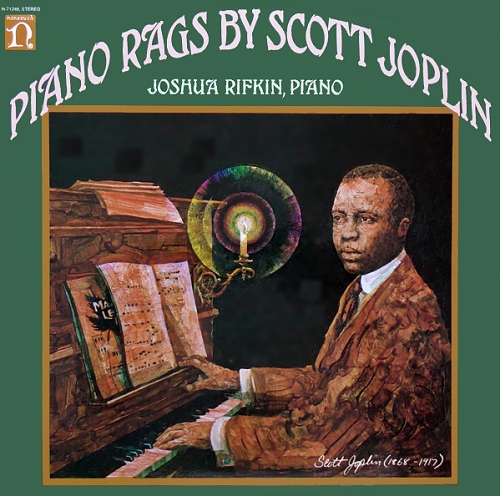

Scott Joplin, who was dubbed "The King of Ragtime Writers" early in his composing career, earned the title through diligence, innovation, and sheer talent. Although he was not entirely responsible for helping lower many of the barriers that stood between black composers and success, Joplin was a leader in this regard, if a passive one. This biography touches on the major points of his life, and does include a lot of independent research by the author. However, it is only a subset of Dr. Ed Berlin's authoritative book on Joplin, King of Ragtime, which is a highly recommended source for those interested in Joplin and his publishing champion, John Stark.

Early Years - Finding a Footing

Scott was born in eastern Texas near Linden. The true birth date is unknown, and the common one of November 24 1868 was suggested by his last wife Lottie, although it was likely between July 19. 1867 (the day after the 1870 census listing him as 2 years old) and mid-January of 1868 according to historian and Joplin biographer Ed Berlin. The June 1880 census lists him as 12 years old, further reinforcing this probability, and the 1900 census lists him with an October birth month, although in 1872, a curiosity for certain. Still, based on that record, an October 1867 date seems probable, yet it is possible that even Joplin himself was not certain.

1867 (the day after the 1870 census listing him as 2 years old) and mid-January of 1868 according to historian and Joplin biographer Ed Berlin. The June 1880 census lists him as 12 years old, further reinforcing this probability, and the 1900 census lists him with an October birth month, although in 1872, a curiosity for certain. Still, based on that record, an October 1867 date seems probable, yet it is possible that even Joplin himself was not certain.

1867 (the day after the 1870 census listing him as 2 years old) and mid-January of 1868 according to historian and Joplin biographer Ed Berlin. The June 1880 census lists him as 12 years old, further reinforcing this probability, and the 1900 census lists him with an October birth month, although in 1872, a curiosity for certain. Still, based on that record, an October 1867 date seems probable, yet it is possible that even Joplin himself was not certain.

1867 (the day after the 1870 census listing him as 2 years old) and mid-January of 1868 according to historian and Joplin biographer Ed Berlin. The June 1880 census lists him as 12 years old, further reinforcing this probability, and the 1900 census lists him with an October birth month, although in 1872, a curiosity for certain. Still, based on that record, an October 1867 date seems probable, yet it is possible that even Joplin himself was not certain.The future composer grew up in the uncertain era of reconstruction. His father, Giles Joplin (sometimes spelled Jiles), was a slave who was freed before the Civil War, and his mother, Florence Givens, was freeborn. He had four other siblings, including older brother Monroe (1861), Robert (3/1869), Josie (1870), William (1875) and Johnny (3/1880). During Scott's first few years, his parents worked as tenant farmers in East Texas. As the family grew, Giles got a job with the railroad in Texarkana, and Florence took up house cleaning and taking in laundry. Both parents were musical, and Scott learned to play the banjo at an early age. His obvious inherent musical talent earned him offers from area piano teachers to tutor him for free. One in particular, Mr. Julius Weiss, gave Scott a solid foundation of not only piano performance skills but an appreciation for classical music forms.

By the age of 12 he was competent at both interpreting and writing music. His father left home around that time to take up residence with another woman, but stayed minimally involved to some extent in Scott's life. In the June 17/18, 1880 Federal census taken in Bowie, Texas, Giles is shown as still residing with the family, working as a common laborer, but he may have left within the year. The same record shows Florence and oldest son Monroe working as well, with Scott and Robert in school. The youngest Joplin, Johnny, was only 3 months old when the census was taken in mid-June, and the youngest three were recorded by the enumerator as having the measles. Scott helped his mother raise his siblings, but always followed his passion for music. There are suggestions by Ed Berlin that during his mid to late teens he spent some time in Sedalia, likely with a relative, but came back at some point to Texarkana. Around age 19 or 20 he left home for good.

Scott spent the next few years as an itinerant pianist, developing his own style while absorbing influences of other Midwest musicians. He spent a great deal of time based in St. Louis, and went to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition (World's Fair) in 1893. It was here that ragtime music, then in its infancy, was most likely heard by the public, and by many other musicians as well for the first time. While it is very unlikely it was played at one of the exhibition's main musical venues, there were certainly a number of establishments just outside the fairgrounds with pianos and no shortage of willing performers. There is no confirmation that Joplin performed anything much less ragtime at the event, or even that he knew any; simply that he was most likely exposed to it to some degree in Chicago.

He spent a great deal of time based in St. Louis, and went to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition (World's Fair) in 1893. It was here that ragtime music, then in its infancy, was most likely heard by the public, and by many other musicians as well for the first time. While it is very unlikely it was played at one of the exhibition's main musical venues, there were certainly a number of establishments just outside the fairgrounds with pianos and no shortage of willing performers. There is no confirmation that Joplin performed anything much less ragtime at the event, or even that he knew any; simply that he was most likely exposed to it to some degree in Chicago.

He spent a great deal of time based in St. Louis, and went to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition (World's Fair) in 1893. It was here that ragtime music, then in its infancy, was most likely heard by the public, and by many other musicians as well for the first time. While it is very unlikely it was played at one of the exhibition's main musical venues, there were certainly a number of establishments just outside the fairgrounds with pianos and no shortage of willing performers. There is no confirmation that Joplin performed anything much less ragtime at the event, or even that he knew any; simply that he was most likely exposed to it to some degree in Chicago.

He spent a great deal of time based in St. Louis, and went to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition (World's Fair) in 1893. It was here that ragtime music, then in its infancy, was most likely heard by the public, and by many other musicians as well for the first time. While it is very unlikely it was played at one of the exhibition's main musical venues, there were certainly a number of establishments just outside the fairgrounds with pianos and no shortage of willing performers. There is no confirmation that Joplin performed anything much less ragtime at the event, or even that he knew any; simply that he was most likely exposed to it to some degree in Chicago.After the fair, Scott made another appearance in Sedalia with his friend Otis Saunders. He remained there for several months, lodging in the Marshall family home, where he first met young Arthur Marshall at age 13. While based in Sedalia, over the next couple of years he formed various bands and singing groups, including the eight member Texas Medley Quartette which featured his two of his younger brothers, Robert and Will. From 1894 to at least 1896 they toured part of the central and eastern United States. During his travels, Joplin managed to get two of his earliest pieces published, including a maudlin song named Please Say You Will.

His first instrumental works included two typical waltzes of the period, and one ambitious march. A descriptive piece in a style that would soon be the domain of composer E.T. Paull, who was already gaining fame for his Chariot Race or Ben Hur March, Joplin's The Great Crush Collision was intended to emulate a leisurely afternoon journey ending in a horrific train wreck. In reality, it was composed to commemorate a wreck staged by agent William George Crush of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) railroad line in Texas on September 15, 1896. That afternoon did not go quite as planned. With around 40,000 spectators in attendance to watch the spectacle, it was inevitable that at least two would be killed by the boiler explosion following the crash. Joplin's march was published soon afterwards in Temple, Texas. While it has few descriptive titles in it, there is detailed text denoting the passage with the fatal wreck of the trains speeding towards each other at 60 miles per hour. Whether the piece was perhaps commissioned by the publisher or was just opportunism is unknown.

Missouri - The Rise to Fame

After spending a little more time on the road, Joplin settled for a time in Sedalia, Missouri in late 1896, a move that would change his life. Sedalia was a busy and important railhead in western Missouri, and also the endpoint of a major cattle trail, so the town was usually full of visitors from all over the region. Already a published composer with five pieces to his credit, Scott attended the George R. Smith College (founded to encourage higher education for African Americans) to further his musical knowledge. Marshall may have also attended with him once he turned 14. While it has been postulated that he took courses to learn how to more accurately notate syncopation, a necessity for correctly writing down his ragtime compositions for others to play, given his previous experience his course study at Smith may have been more for advanced harmony and theory, an enrichment of his current knowledge base.

Already a published composer with five pieces to his credit, Scott attended the George R. Smith College (founded to encourage higher education for African Americans) to further his musical knowledge. Marshall may have also attended with him once he turned 14. While it has been postulated that he took courses to learn how to more accurately notate syncopation, a necessity for correctly writing down his ragtime compositions for others to play, given his previous experience his course study at Smith may have been more for advanced harmony and theory, an enrichment of his current knowledge base.

Already a published composer with five pieces to his credit, Scott attended the George R. Smith College (founded to encourage higher education for African Americans) to further his musical knowledge. Marshall may have also attended with him once he turned 14. While it has been postulated that he took courses to learn how to more accurately notate syncopation, a necessity for correctly writing down his ragtime compositions for others to play, given his previous experience his course study at Smith may have been more for advanced harmony and theory, an enrichment of his current knowledge base.

Already a published composer with five pieces to his credit, Scott attended the George R. Smith College (founded to encourage higher education for African Americans) to further his musical knowledge. Marshall may have also attended with him once he turned 14. While it has been postulated that he took courses to learn how to more accurately notate syncopation, a necessity for correctly writing down his ragtime compositions for others to play, given his previous experience his course study at Smith may have been more for advanced harmony and theory, an enrichment of his current knowledge base.Joplin performed in many area venues during this time both as a solo performer and with varying sizes of groups playing either piano or cornet. Among those was the well-regarded Queen City Concert Band, who often did concerts in Pettis County and surrounding areas. There were also many dance organizations to play for as well, including the Manhattan Dancing Club, the Autumn Leaf Club, and the Black 400, which was run by Tony and Charles Williams. Scott further acted as a mentor for many of the younger black musicians in town, who would often congregate at the Marshall home for instruction and inspiration.

Scott's first piano rag publication came in early 1899. He had submitted a work to Kansas City, Missouri publisher Carl Hoffman. It was endorsed by Hoffman's young staff composer and whiz kid Charles N. Daniels, who received an "arranged by" credit on the cover. There is no clear evidence, based on Daniel's work or his later recollections, that Charles arranged anything more than to have it published. There have also been stories that Joplin submitted another fine rag to Daniels but that it was rejected as too difficult, but again such stories are hard to confirm, even if they are plausible. Scott's next move towards greatness was back in Sedalia. It was while working in one of the many drinking and gathering establishments in Sedalia in the summer of 1899, the short-lived (December 1898 to January 1900) Maple Leaf Club, that Scott allegedly became involved with one of his greatest champions, music store owner John Stark, and at the very least where he found the name for his first truly inspired rag. The club was run by Walker and Will Williams, and located on the second floor of 121 East Main, just over a block east of the primary downtown route, Ohio Street.

How Joplin actually presented the piece to Stark has also become a point of legend. In any event, Stark, who had acquired some publications from another source and was considering putting out some of his own, was impressed enough by Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag that he quickly took it on, giving the composer a royalty (.01¢ per copy). This was very unusual at this time, more so since Joplin was a black composer working with a white publisher. Since it was likely a lawyer friend of Joplin's that helped make the contact with Stark and drew up the contract, it may have been a mutually agreed upon point that not only provided protection for both parties, but would eventually alter Joplin's financial well-being, allowing him to spend more time composing. Stark further encouraged Joplin to bring him more compositions, of which the collaborative Sunflower Slow Drag may have been submitted around the same time. The Maple Leaf Rag, published in Sedalia but printed and distributed in St. Louis as well, was nearly an instant hit locally, and over the next two decades it reportedly became the first piano rag to sell a million copies, although when that mark was reached is unclear. Although the relationship between Stark and Joplin would often be strained over much of the next 18 years, the publisher always promoted Joplin's works as the finest in his catalog. Those periods of animosity between them are in part demonstrated by name of varying publishers whose imprints appear at the bottom of each new Joplin rag.

Since it was likely a lawyer friend of Joplin's that helped make the contact with Stark and drew up the contract, it may have been a mutually agreed upon point that not only provided protection for both parties, but would eventually alter Joplin's financial well-being, allowing him to spend more time composing. Stark further encouraged Joplin to bring him more compositions, of which the collaborative Sunflower Slow Drag may have been submitted around the same time. The Maple Leaf Rag, published in Sedalia but printed and distributed in St. Louis as well, was nearly an instant hit locally, and over the next two decades it reportedly became the first piano rag to sell a million copies, although when that mark was reached is unclear. Although the relationship between Stark and Joplin would often be strained over much of the next 18 years, the publisher always promoted Joplin's works as the finest in his catalog. Those periods of animosity between them are in part demonstrated by name of varying publishers whose imprints appear at the bottom of each new Joplin rag.

Since it was likely a lawyer friend of Joplin's that helped make the contact with Stark and drew up the contract, it may have been a mutually agreed upon point that not only provided protection for both parties, but would eventually alter Joplin's financial well-being, allowing him to spend more time composing. Stark further encouraged Joplin to bring him more compositions, of which the collaborative Sunflower Slow Drag may have been submitted around the same time. The Maple Leaf Rag, published in Sedalia but printed and distributed in St. Louis as well, was nearly an instant hit locally, and over the next two decades it reportedly became the first piano rag to sell a million copies, although when that mark was reached is unclear. Although the relationship between Stark and Joplin would often be strained over much of the next 18 years, the publisher always promoted Joplin's works as the finest in his catalog. Those periods of animosity between them are in part demonstrated by name of varying publishers whose imprints appear at the bottom of each new Joplin rag.

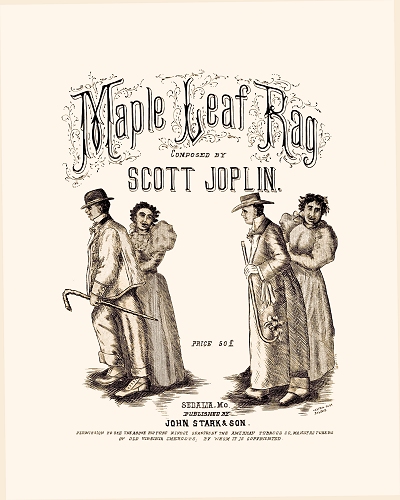

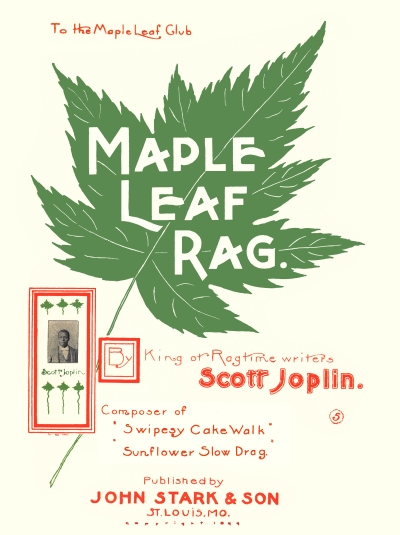

Since it was likely a lawyer friend of Joplin's that helped make the contact with Stark and drew up the contract, it may have been a mutually agreed upon point that not only provided protection for both parties, but would eventually alter Joplin's financial well-being, allowing him to spend more time composing. Stark further encouraged Joplin to bring him more compositions, of which the collaborative Sunflower Slow Drag may have been submitted around the same time. The Maple Leaf Rag, published in Sedalia but printed and distributed in St. Louis as well, was nearly an instant hit locally, and over the next two decades it reportedly became the first piano rag to sell a million copies, although when that mark was reached is unclear. Although the relationship between Stark and Joplin would often be strained over much of the next 18 years, the publisher always promoted Joplin's works as the finest in his catalog. Those periods of animosity between them are in part demonstrated by name of varying publishers whose imprints appear at the bottom of each new Joplin rag.Of some interest is the progression of Maple Leaf Rag editions that have been in more or less continuous print since 1899. The first, likely printed in St. Louis and distributed there and Sedalia, and places in between, featured a drawing based on a tobacco advertising sketch from the American Tobacco Company. The dancers depicted on the cover are none other than famous black vaudeville stars George Walker and Bert Williams and their wives dancing the cakewalk. After perhaps 400 copies had been printed, the cover was changed to the common and more familiar Maple Leaf in 1900. The dedication remained even though the venue was closed by that time. The first of these editions had a picture of Joplin on the lower left side. Subsequent editions filled this area with a random pattern. It may be extrapolated that even though Stark did not outwardly demonstrate racism in his embracing of ragtime, some of his customers may have. Therefore, the removal of Joplin's picture identifying him as a black composer rather than suggest an anonymous one may have been simply a business decision to make this increasingly popular rag easier to sell in certain parts of the country. There would be virtually no other reason to change this plate unless the original lithograph was broken. That may have happened at a later time as in the 1920s and beyond there are a couple of mild variations of the famous cover leaf.

That may have happened at a later time as in the 1920s and beyond there are a couple of mild variations of the famous cover leaf.

That may have happened at a later time as in the 1920s and beyond there are a couple of mild variations of the famous cover leaf.

That may have happened at a later time as in the 1920s and beyond there are a couple of mild variations of the famous cover leaf.In the 1900 census Joplin was listed as a musician, with his birth date curiously recorded as October of 1872, and his age as 27. He was lodging in the home of Susan H. Hankins, who was also hosting Belle Hayden Jones, the recently widowed sister-in-law of one of his young students, Scott Hayden. The only 1900 publication with Joplin's name on it was a collaboration with his student Arthur Marshall. Swipesy Cake Walk was relatively advanced for that time, and more of a foot-stomping rag than a cakewalk. Mostly the work of his student, Joplin is suspected of having contributed the trio section. This publication helped to solidify Joplin's name as a piano rag composer, and gave Marshall a foot in the door. Sunflower Slow Drag, composed with Scott Hayden and possibly submitted even before Swipesy, was published in 1901. As with Swipesy, Joplin most likely contributed the trio and a few edits elsewhere. Knowing that waltzes were still popular, Joplin wrote and dedicated the Augustan Club Waltzes to the white Augustain Club of Sedalia in early 1900. Possibly a commissioned piece, it was possibly first performed a special ball held by the club that February. However, Stark did not print the piano solo of Augustan Club Waltzes until 1901.

With the publishing business expanding in late 1899, John Stark left the store in Sedalia under the management of Will and moved to St. Louis to open a music store and a furniture moving business. It is probable that the first edition of Maple Leaf Rag had been printed there by a jobber, and as he was to take on more works (including some by his son Etilmon J. Stark), it made more sense to be in a city with better access to printing facilities and distribution. After another year and a half in Sedalia, Scott decided to make the same move. He was likely aware of the bustling ragtime scene in St. Louis, and the coming of the Lewis and Clark Exposition and World's Fair, due to open in 1903. Just before he moved to St. Louis in late 1901, Joplin (as some evidence suggests) possibly married Belle Hayden, and it may have also been a common-law marriage. The couple settled in St. Louis and Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden, along with his new bride Nora Hayden, soon followed them there for a while, even staying with the couple.

The couple settled in St. Louis and Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden, along with his new bride Nora Hayden, soon followed them there for a while, even staying with the couple.

The couple settled in St. Louis and Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden, along with his new bride Nora Hayden, soon followed them there for a while, even staying with the couple.

The couple settled in St. Louis and Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden, along with his new bride Nora Hayden, soon followed them there for a while, even staying with the couple.St. Louis in 1901 was a bustling locale musically, and it was home of the first published piano rag composed by a Negro, Harlem Rag by Tom Turpin. Turpin ran a number of different saloon enterprises along with his father and brother, and at his own Rosebud Cafe featured ragtime performers from all over, and even the occasional competition. Among the other St. Louis performers were the diminutive and highly talented Louis Chauvin, his friend Sam Patterson, and future entrepreneur and prolific composer Joe Jordan. When Joplin came to town, his growing legacy of fine compositions made him a near-instant celebrity among his peers, and even white reviewers and others in the St. Louis population took notice.

One in particular was Alfred Ernst, director of the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society. He was a German musician who had somehow met with Joplin and appeared to understand the complexities and fine construction of his works. In a newspaper article printed in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of February 28, 1901, even before Joplin had officially moved to that city, Ernst talked about taking Joplin pieces to Germany for performance, and even taking the composer himself to play. There is no evidence that such a trip ever took place, but it did help increase the level of respect that Scott had been earning as a composer, and perhaps even as a performer of ragtime.

The contention that Joplin was a brilliant pianist should be abandoned based on a number of reports from his lifetime. He was regarded by many as not poor, but certainly adequate in his playing skills. However, he rarely earned money performing as a soloist, and even made a point of not frequenting many of the notorious venues where other ragtime and barrelhouse pianists were often found. When he was in need of funds, Joplin would play for special events and private parties, and perhaps at the request of Turpin when occasionally at one of his bars. Otherwise, he was evidently more than adequate at teaching both piano technique and music skills, even though his temperament of later years impeded these efforts somewhat. It appears that most of Scott's revenue was generated by royalties from his compositions and the occasional commissioned work.

Success and Heartbreak

The period of 1901 to 1902 was one of the first that found Joplin at odds with Stark. In late 1901 he had The Easy Winners published in St. Louis by Shattinger Music. Even though the title and the cover art represented sporting events and had the connotation of gambling, something that Stark did not endorse in his beliefs, Stark eventually acquired the piece from Shattinger for subsequent editions. Another fine work from the same time was his Peacherine Rag. Marches were still in vogue as well, so the first Joplin work of 1902 to be published was the march Cleopha. A second march from the same year was the less inspired March Majestic.

Among the standout Joplin rags of 1902 was The Entertainer, which was dedicated to James Brown and his Mandolin Club. Such clubs were quite popular during the ragtime era. It could be construed in the literal sense as the musical imitation of a comedic entertainer. In the first section with its call and response construction, it could be asking "why did the chicken cross the road?" The response would be "to get to the other side." It was a memorable and popular work in St. Louis, and would of course become even more popular in the 1970s when it was used as the primary theme for the Universal picture, The Sting. Another fine rag was The Strenuous Life, the title which came from a collection of essays published in 1900 by then-vice presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt. Joplin held Roosevelt, who had since gained the presidency through the assassination of William McKinley, in very high regard as would soon be demonstrated by his first major stage work. Another rag from that time, A Breeze From Alabama, has remained popular into the 21st Century, particularly as a band work.

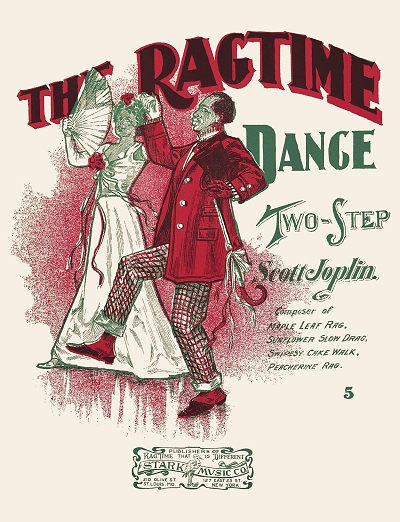

The next major flap between Joplin and Stark was over the publication of an extended rag ballet intended for stage or social events, which had evidently been performed as early as 1899 in Sedalia. Stark resisted taking the work on, knowing that it had only a limited sales potential. However, he grudgingly published this long version of The Ragtime Dance, which had been orchestrated and performed in St. Louis as well by this time, due largely to the prompting of his daughter Eleanor. The piece sold poorly as the elder Stark expected. Still, with profits from the other fine rags in his catalog, John Stark was able to open a music store and publishing plant in St. Louis.

The piece sold poorly as the elder Stark expected. Still, with profits from the other fine rags in his catalog, John Stark was able to open a music store and publishing plant in St. Louis.

The piece sold poorly as the elder Stark expected. Still, with profits from the other fine rags in his catalog, John Stark was able to open a music store and publishing plant in St. Louis.

The piece sold poorly as the elder Stark expected. Still, with profits from the other fine rags in his catalog, John Stark was able to open a music store and publishing plant in St. Louis.Joplin wrote an early ragtime opera in two acts, which finished in 1903 and titled A Guest of Honor. The story was likely based on a formal visit to the Roosevelt White House by black scholar Booker T. Washington, which had been famously protested by many members of Congress from the South. Joplin formed a touring company of over thirty for the show which included Marshall and Hayden. Once Joplin had secured financing, the show debuted in St. Louis on August 30, and he then toured with it briefly in the late summer and fall of 1903. The planned tour included stops in Sedalia, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas. However, they did not make it beyond Springfield, Illinois, when some form of financial misfortune of an unknown nature occurred even before the first week was out.

The company evidently moved on to a few more stops, where it possibly ended in Pittsburg, Kansas. According to a story told by Lottie Joplin, the score was left in a trunk in Pittsburg. Ed Berlin speculated that this might possibly been the result of a seizure of the company's assets for the inability to pay their debts. Although no score has been re-discovered, remnants potentially remain in the form of a rag and march, and some titles from are known at the very least, including Antoinette, a march published in 1906. Also mentioned but never found were Dude's Parade and Patriotic Patrol, the latter of which may have been a militaristic stage drill. Another piece possibly completed during the Chicago visit of the tour was an arrangement of the song Little Black Baby by Louise Armstrong Bristol, which actually credits Joplin as the composer of the music, although that status is uncertain.

To add to Joplin's troubles, there is a possibility that he and Belle had been at odds for some time in St. Louis. He had hoped to engage her in his music by teaching her violin, but she turned out to have no aptitude for the instrument. After they had a baby girl that died at two months, the couple became estranged, then separated. Belle later moved away from St. Louis, ending their relationship. Contrary to some previously published information that perhaps confused Belle Hayden with Scott's second wife, she lived until 1930 or so. Since no official divorce is on record for them, this further reinforces the notion of theirs potentially being a common law marriage.

Contrary to some previously published information that perhaps confused Belle Hayden with Scott's second wife, she lived until 1930 or so. Since no official divorce is on record for them, this further reinforces the notion of theirs potentially being a common law marriage.

Contrary to some previously published information that perhaps confused Belle Hayden with Scott's second wife, she lived until 1930 or so. Since no official divorce is on record for them, this further reinforces the notion of theirs potentially being a common law marriage.

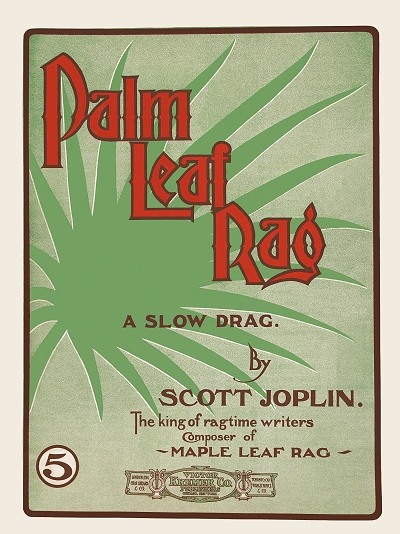

Contrary to some previously published information that perhaps confused Belle Hayden with Scott's second wife, she lived until 1930 or so. Since no official divorce is on record for them, this further reinforces the notion of theirs potentially being a common law marriage.In spite of the energy that the opera and the tour required, Scott managed to have three rags published in 1903. Something Doing with Hayden may have been from the previous year. He placed the engaging and sanguine Weeping Willow Rag with publisher Val A. Reis, and possibly while in Chicago submitted his Palm Leaf Rag to rag-centric publisher Victor Kremer. The latter is also a favorite with ragtime orchestras over a century later. His most famous work was retrofitted, as were many instrumental hits of the time, with lyrics. Stark released Maple Leaf Rag as a song with coon-type lyrics by Sydney Brown, a move likely unauthorized by the composer, but over which he had little control. Given his largely dignified and pacifist demeanor, it is unlikely that he would have wanted the inclusion of potential razor blade fights and other stereotypical references associated with his famous rag. The original Maple Leaf Rag was also recorded for the first time in 1903 by clarinetist and composer Wilbur Sweatman, but the original cylinder has long been lost.

At some point after the financially disastrous Guest of Honor tour, Joplin spent up to a few months in Chicago before returning to St. Louis. By the time the Lewis and Clark Exposition and World's Fair opened there in late April 1904, nearly a year after the original projected launch, he was probably back in Sedalia where he briefly settled. Many African-American musicians and prominent citizens had lobbied for their own pavilion at the fair. However, some opponents conjectured that it would further segregate them from the majority of attendees who were white, so the effort was abandoned. Black performers were still easily found in the vicinity during the run of the fair, particularly on the mile long entertainment street known as The Pike.

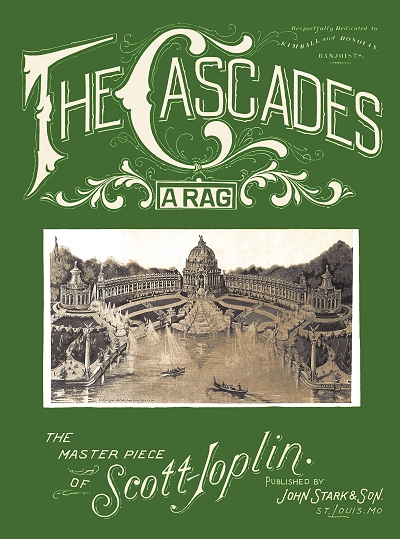

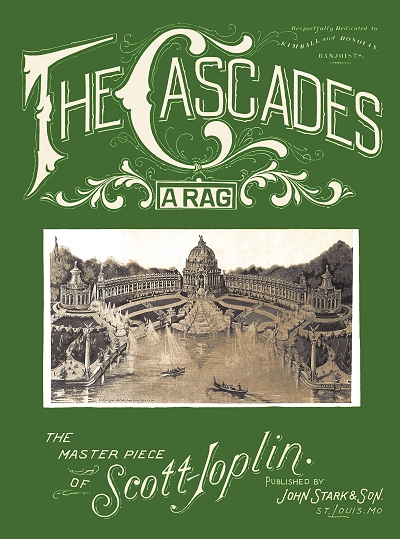

Joplin was given an opportunity to play at the exposition, but his presence was overshadowed by many larger groups, including the legendary band of John Philip Sousa. He was one of many composers who wrote a work specifically for the exposition, giving the world The Cascades, a musical celebration and emulation of the waterfalls that extended out behind the Hall of Music on the fairgrounds. John Stark published The Cascades and wrote ebullient ad copy about it in the papers. "Hear it, and you can fairly feel the earth wave under your feet. It is as high-class as Chopin and is creating a great sensation among musicians. This piece, Tom Turpin's St. Louis Rag, and the extremely catchy Meet Me In St. Louis by composer Frederick Allen Mills are the three pieces from that event that have endured the longest.

and the extremely catchy Meet Me In St. Louis by composer Frederick Allen Mills are the three pieces from that event that have endured the longest.

and the extremely catchy Meet Me In St. Louis by composer Frederick Allen Mills are the three pieces from that event that have endured the longest.

and the extremely catchy Meet Me In St. Louis by composer Frederick Allen Mills are the three pieces from that event that have endured the longest.Other rags from 1904 included The Sycamore, a "concert rag" published in Chicago by Will Rossiter, likely submitted before his return to Sedalia. Also released was The Favorite, published in Sedalia by the other house, that of A.W. Perry who released a number of other ragtime works. This publication is curious as Joplin would likely not have gone with the smaller publisher by this time. However, Ed Berlin noted that Brun Campbell, a white pupil of Joplin's who had been in Sedalia in 1898 and 1899, stated that The Favorite was likely sold to Perry at that time. While the four year delay in releasing it is hard to explain, there is some potential credibility to that story.

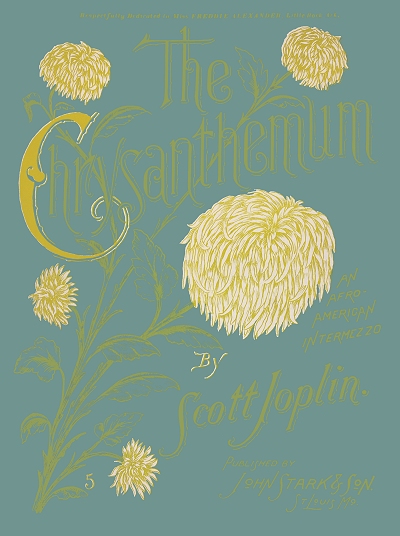

Then there was the heartfelt masterpiece of 1904, The Chrysanthemum, published by Stark. The categorical status of this piece has long been under debate. The description of it given by the composer is "an Afro-Intermezzo." While there is nominally enough syncopation in the work to count it as a piano rag, historian Dave Jasen has maintained, with validity, that it is an intermezzo, a non-syncopated type of piece that lies in limbo between the march and the song, but is usually in ragtime form. This affecting piece has some of the hallmarks of European piano forms with Joplin's signature harmonic patterns and melodic flow, and an unusual but effective interlude that is a full sixteen bars in length. But there is another association to be made with this musical floral tribute.

Unknown for a number of years, but uncovered and researched by Ed Berlin for his book King of Ragtime, curing this period (perhaps even before) Scott somehow met a 19 year-old girl in Little Rock, Arkansas that had captured his heart. He subsequently married Freddie Alexander, to whom he had dedicated the first printing of the Chrysanthemum, on June 14, 1904. The couple then traveled back to Sedalia from Little Rock, with Scott playing concerts along the way. However, as soon as they reached Sedalia in July, Freddie took ill and was confined to bed for a cold that developed into pneumonia. The illness took her life in early September after they had been married less than three months. The details of Freddie's history have been difficult to unearth, and her burial information was lost in a subsequent courthouse fire. Ed Berlin, with a legion of volunteers, sought out her tombstone in Sedalia in 1988. However, she was possibly returned to Little Rock by her sister Lovie Alexander, and is just as likely to have been buried there.

The details of Freddie's history have been difficult to unearth, and her burial information was lost in a subsequent courthouse fire. Ed Berlin, with a legion of volunteers, sought out her tombstone in Sedalia in 1988. However, she was possibly returned to Little Rock by her sister Lovie Alexander, and is just as likely to have been buried there.

The details of Freddie's history have been difficult to unearth, and her burial information was lost in a subsequent courthouse fire. Ed Berlin, with a legion of volunteers, sought out her tombstone in Sedalia in 1988. However, she was possibly returned to Little Rock by her sister Lovie Alexander, and is just as likely to have been buried there.

The details of Freddie's history have been difficult to unearth, and her burial information was lost in a subsequent courthouse fire. Ed Berlin, with a legion of volunteers, sought out her tombstone in Sedalia in 1988. However, she was possibly returned to Little Rock by her sister Lovie Alexander, and is just as likely to have been buried there.This tragedy started a period of compositional malaise and possibly depression for the composer. Subsequent printings of Chrysanthemum had the dedication to the now deceased Freddie removed. For the remainder of 1904 he was difficult to find, but soon moved back to St. Louis by early 1905. Joplin re-established his relationships with Turpin, Chauvin and Patterson. Marshall had moved back to Sedalia with his new wife. In the 1950 book They All Played Ragtime by Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, the claim was made that young composer James Scott of Carthage, Missouri, made his way to St. Louis to meet the ragtime players there, and ideally Joplin himself. While there is no direct evidence that they actually got together, there are circumstantial bits suggesting it, including the association of Joplin with Frog Legs Rag. He had arranged Scott's best-selling piece for band, which was published in Standard High Class Rag, better known as The Red Back Book. However, James Scott spent most of his time in western Missouri, and later Kansas City, so opportunities for an ongoing Joplin/Scott relationship were rather scant.

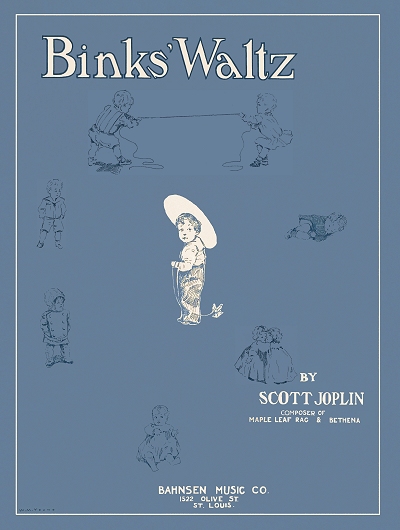

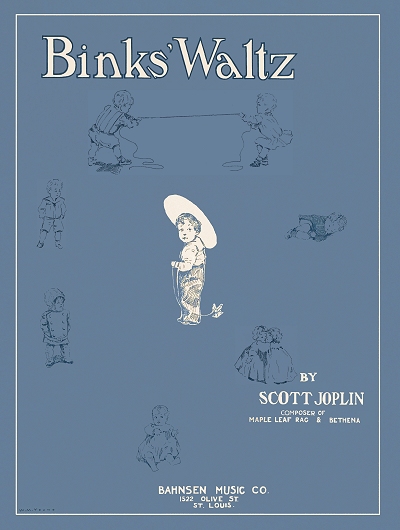

Joplin's next work was published in the spring of 1905. Bethena was published by a local piano manufacturer, the T. Bahnsen Piano Company of St. Louis. It is a brooding waltz reminiscent of some of the works of Brahms, who Joplin had likely studied in prior years. The piece was dedicated to a Mr. and Mrs. Dan E. Davenport of St. Louis, who may have helped him through his mourning period, and even set up publication with Bahnsen. Ed Berlin brings up the intriguing possibility that the girl pictured on the cover could potentially be Freddie Joplin. It could also be Bethena, but even though many Bethenas have been found in the census, none could be pinpointed as the namesake of the piece.

Bahnsen also published a song Joplin wrote to lyrics by Henry Jackson, Sarah Dear, a ragtime song either commissioned by or written for the comedy team of Williams and Stevens, who traveled on the T.O.B.A. vaudeville circuit. One other piece published before that was either a commissioned waltz or one written in gratitude to another couple that had helped Joplin. William A. and Anna Morgens, who owned a dry-cleaning operation, had a share in the Bahnsen company. The piece was written for their toddler, James Allen Morgens, who was nick-named "Bing." How Bing was morphed into Binks is unclear, but the piece was published as the charming non-syncopated Binks' Waltz. The payment structure Joplin had with Bahnsen is unclear, but it was more likely a direct payment for a set quantity than a commission. This would have made sense for works that were not distributed very far beyond St. Louis.

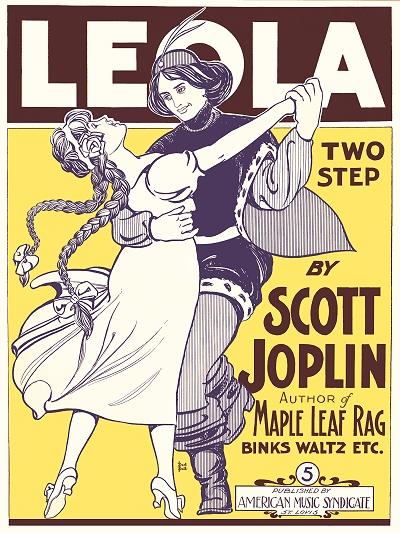

The remaining 1905 works were more mainstream in both composition but not distribution. The Rose-bud March was a musical dedication to the famous Tom Turpin bar where so many early ragtime figures had congregated in St. Louis. A snappy 6/8 march, it had some of the elements of works by John Philip Sousa or Arthur Pryor, yet easily managed on the piano. Stark's company published the work. Leola, on the other hand, was poorly distributed by the little-known American Music Syndicate of St. Louis. The only ad copy found by this company listed an address of 300-302 N. 3rd Street in St. Louis as of July, 1903, when they were advertising Latonia Rag. Leola and Joplin got a raw deal in this instance. It is notable that this is the rag which first printed what is probably Joplin's own admonition: "Notice! Don't play this piece fast. It is never right to play 'rag-time' fast. Author."

By the end of 1905, with the fair long gone and the musical center of the country having shifted north and east, St. Louis had undergone many changes. John Stark had set up shop in New York in an effort to compete with larger publishers who were putting out ragtime inferior (his staunch belief) to what was in his catalog. He left Will in charge of the St. Louis operation. Arthur Marshall had moved to Chicago along with a number of other St. Louis musicians looking for new work in a hopefully less saturated market, although most met with some disappointment in that regard. Joplin, faced with a number of choices that could leave him sinking into obscurity or taking a chance at more exposure chose at that time to follow the crowd to Chicago. His brother Robert was already there, along with Marshall, so he at least had some friendly faces to greet him.

His brother Robert was already there, along with Marshall, so he at least had some friendly faces to greet him.

His brother Robert was already there, along with Marshall, so he at least had some friendly faces to greet him.

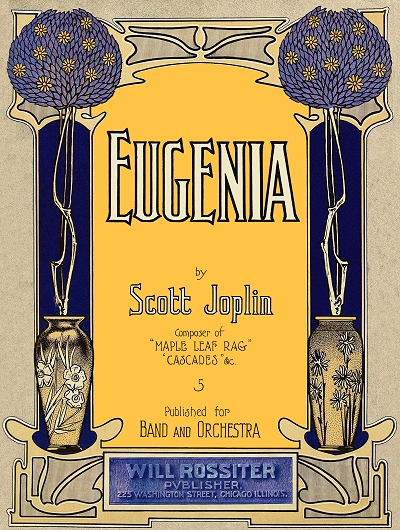

His brother Robert was already there, along with Marshall, so he at least had some friendly faces to greet him.Chicago was certainly a better market for publishers, of which there were many. Joplin already had a relationship with a couple of them. So his first published work of 1906, Eugenia, most likely another flora-themed work named after the eugenia bush pictured on the cover, was taken in by Will Rossiter. It features some patterns and phrasing that were similar to the newer European impressionist composers, and had an overall flow that showed an advance in direction from his prior rags.

One of the coming music trends in both the home and in public was that of automated music. By 1906 pushup piano players had been internalized, and player pianos were starting to hit the streets. Joplin was able to capitalize on his fame and use it for an endorsement, most likely one that reciprocated with some compensation of some kind, for one of the more popular player systems of the time, the Apollo Player Piano. The company was among the first big successes in the business, and they touted Joplin's endorsement to their peers in the November 10, 1906 edition of the Music Trade Review:

The following letter was received by the Kieselhorst Piano Co. from Scott Joplin, a prominent local composer, under date of Nov. 5:

"I want to thank you for your kindness in having my compositions arranged for the Apollo. Out of all the piano players that I have heard my pieces played on, the Apollo always has the best arrangement, and the music seems to be more perfect and cleaner cut. I also like the arrangement of my compositions when played on the Apollo Grand, as the couplers give it much more harmony and make it more like an orchestral arrangement."

Louis Chauvin and Sam Patterson also ventured up to Chicago at some point in 1906. Chauvin was starting to deteriorate physically and mentally. Although a number of medical theories have been put forward, a recent and more astute (although non-professional) diagnosis, which would explain his diminutive height and yellowish coloring, would be that he suffered from sickle cell anemia. After a life of hard drinking and less than safe sex, a toll was extracted on the brilliant performer's body. It was during their concurrent stay in Chicago that Scott and Louis exchanged ideas for a couple of themes that had been running through Chauvin's head. Louis went back to St. Louis later that summer, but returned to Chicago in 1907.

After a life of hard drinking and less than safe sex, a toll was extracted on the brilliant performer's body. It was during their concurrent stay in Chicago that Scott and Louis exchanged ideas for a couple of themes that had been running through Chauvin's head. Louis went back to St. Louis later that summer, but returned to Chicago in 1907.

After a life of hard drinking and less than safe sex, a toll was extracted on the brilliant performer's body. It was during their concurrent stay in Chicago that Scott and Louis exchanged ideas for a couple of themes that had been running through Chauvin's head. Louis went back to St. Louis later that summer, but returned to Chicago in 1907.

After a life of hard drinking and less than safe sex, a toll was extracted on the brilliant performer's body. It was during their concurrent stay in Chicago that Scott and Louis exchanged ideas for a couple of themes that had been running through Chauvin's head. Louis went back to St. Louis later that summer, but returned to Chicago in 1907.It was in 1907 that Joplin would complete a rag based on Chauvin's two themes and submit it for publication, ostensibly to help benefit his ailing colleague. Heliotrope Bouquet, published by Stark, remains one of the most haunting rags that Joplin was associated with. It is likely that Louis wrote the A and B sections, while Scott finished it out, utilizing some of the Chauvin themes in both the trio and D sections. Louis Chauvin would die several months later in March 1908, partially from starvation due to a coma, and the rest from simply being worn out by disease.

Before that, however, Joplin returned to St. Louis late in the summer of 1906, but his activities in public were minimal. Two more pieces would be published late in the year. Antoinette, a 6/8 march that was possibly a remnant of A Guest of Honor, was published by Stark in St. Louis, who may have had it in their office for some time. With some editing by somebody at the Stark company, The Ragtime Dance was repurposed into a half-stoptime rag, trimmed a bit from its original 1902 edition by excising the extended verse and removing some of the repeats.

In early 1907 Scott relocated to Clayton, a suburb of St. Louis, and spent time with white musician Harry LaMertha. Out of this relationship came the piece Snoring Sampson: A Quarrel in Ragtime, which Joplin arranged. Another song appeared in the spring, When Your Hair is Like the Snow, with music by Joplin composed to lyrics by publisher Owen Spendthrift.

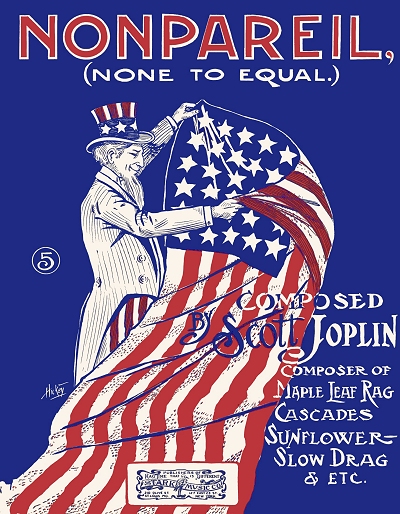

In terms of piano rags, the earliest of the year was Nonpareil (None to Equal). The source of the title is unknown. Well known 1880s pugilist Jack Dempsey had gone by the French-derived title of Non-Pareil, but by 1907 any memory of his work might have faded. There were also performing groups and venues that used the same name. The cover gives a clue with a picture of Uncle Sam unfurling an American flag. Whether Joplin or Stark named it might also be a point of speculation. It featured one of the most developed and mature trios to date, with a lot of left-hand motion. John Stark, who had been commuting regularly between New York and St. Louis, published the rag. Whether he had anything to do with Joplin's next move is uncertain, but Stark was likely a factor in it. After an early summer visit to his family in Texarkana, and another to Chicago to see Marshall one last time, Joplin followed Stark's lead and relocated to New York to be closer to opportunities that could forward his music career, never to return to the Midwest.

New York and New Horizons

Some of Scott Joplin's best-developed works are from the period 1907 to 1910, and they demonstrate the versatility of classic ragtime as well as a variety of textures that could be achieved within that framework. Even before he left St. Louis he had mentioned that he was working on another opera utilizing older Negro themes. This was likely the early development of Treemonisha, which would later nearly consume him. But for now, he needed to focus on getting down to business. His first residence was in a boarding house on 29th Street, which was a couple of blocks from Tin Pan Alley, at that time located on 28th Street just to the west of Broadway. It was in the tenderloin district, but also in close proximity to a number of Broadway theaters. He was also less than a mile from Stark's New York office on 23rd Street. Many of local venues featured black entertainers either in vaudeville, stage musicals, or musicians playing in restaurants, including some performers that Joplin had met in St. Louis, such as Joe Jordan.

Even before he left St. Louis he had mentioned that he was working on another opera utilizing older Negro themes. This was likely the early development of Treemonisha, which would later nearly consume him. But for now, he needed to focus on getting down to business. His first residence was in a boarding house on 29th Street, which was a couple of blocks from Tin Pan Alley, at that time located on 28th Street just to the west of Broadway. It was in the tenderloin district, but also in close proximity to a number of Broadway theaters. He was also less than a mile from Stark's New York office on 23rd Street. Many of local venues featured black entertainers either in vaudeville, stage musicals, or musicians playing in restaurants, including some performers that Joplin had met in St. Louis, such as Joe Jordan.

Even before he left St. Louis he had mentioned that he was working on another opera utilizing older Negro themes. This was likely the early development of Treemonisha, which would later nearly consume him. But for now, he needed to focus on getting down to business. His first residence was in a boarding house on 29th Street, which was a couple of blocks from Tin Pan Alley, at that time located on 28th Street just to the west of Broadway. It was in the tenderloin district, but also in close proximity to a number of Broadway theaters. He was also less than a mile from Stark's New York office on 23rd Street. Many of local venues featured black entertainers either in vaudeville, stage musicals, or musicians playing in restaurants, including some performers that Joplin had met in St. Louis, such as Joe Jordan.

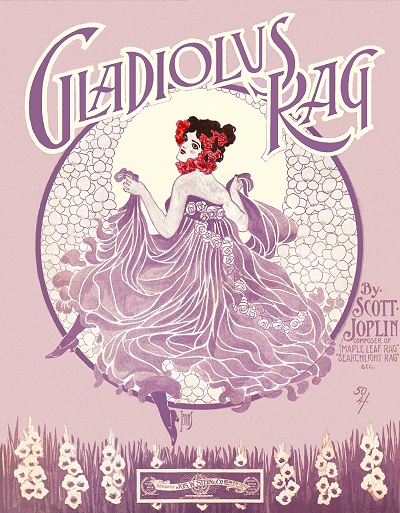

Even before he left St. Louis he had mentioned that he was working on another opera utilizing older Negro themes. This was likely the early development of Treemonisha, which would later nearly consume him. But for now, he needed to focus on getting down to business. His first residence was in a boarding house on 29th Street, which was a couple of blocks from Tin Pan Alley, at that time located on 28th Street just to the west of Broadway. It was in the tenderloin district, but also in close proximity to a number of Broadway theaters. He was also less than a mile from Stark's New York office on 23rd Street. Many of local venues featured black entertainers either in vaudeville, stage musicals, or musicians playing in restaurants, including some performers that Joplin had met in St. Louis, such as Joe Jordan.After a month or so in Manhattan, Joplin turned in two of his masterpieces to publisher Joseph W. Stern, who had been friendly to other black composers. Stern, like Stark, was more likely to have paid royalties, and important point for a composer relying on a meager but steady income. Searchlight Rag, which was a nod to the town of Searchlight, Nevada, where Tom Turpin and his brother had a stake in the Big Onion Mine in the 1890s, followed some of the flow of Nonpareil, but was a little less developed. Gladiolus Rag, however, was close to the pinnacle of his composition career. While it followed the chord progression and symmetry of the Maple Leaf Rag, and even the key signature, the nuances throughout were much more sophisticated than his earlier model, and the dense moving chord progressions in the trio required more skill and understanding of harmony from the pianist than virtually any of his previous efforts.

Another collaboration with Marshall, possibly from 1906, was notated and arranged by Joplin, but Marshall wanted to go elsewhere than Stark for publication based on poor negotiations on a previous rag. So Joplin took it to Willis Woodward for publication. (The cover shows W.W. Stuart, but no other publication under that name could be found, and the address and the name in the title footer indicate Woodward). Even though Marshall claims to have written Lily Queen with no assistance, Ed Berlin and this author believe that Joplin's influence in notating the piece, something that Marshall was much less capable of, was enough to deserve a at least nominal co-author credit. The example of composer Artie Matthews, who also published with Stark, provides enough proof of such an influence, as certain pieces arranged by Matthews clearly contain unique characteristics found only in his few rags.

The example of composer Artie Matthews, who also published with Stark, provides enough proof of such an influence, as certain pieces arranged by Matthews clearly contain unique characteristics found only in his few rags.

The example of composer Artie Matthews, who also published with Stark, provides enough proof of such an influence, as certain pieces arranged by Matthews clearly contain unique characteristics found only in his few rags.

The example of composer Artie Matthews, who also published with Stark, provides enough proof of such an influence, as certain pieces arranged by Matthews clearly contain unique characteristics found only in his few rags.Then there is the question raised by Rose Leaf Rag, which was taken by Boston, Massachusetts publisher Joseph M. Daly. That Joplin ventured to Boston is possible, but given his limited income flow it may have been more likely that Daly, like many non-New York based publishers, had an agent in Manhattan to buy pieces and stock local stores with Daly sheet music. Rose Leaf Rag is another one of the high points in Joplin's extraordinary 1907 output, with a very delicate first section opening full of contrary and parallel motion between the hands. It is much less dense than the previous three pieces, but allowed pianists of lesser ability the opportunity to master a Joplin rag complete with that so-called "weird and intoxicating" sound.

A meeting of great consequence to the legacy of ragtime occurred in late 1907 at the office of John Stark between Joplin and a younger white accountant who happened to also write ragtime, Joseph Lamb of Montclair, New Jersey. Lamb had been writing for several years, and already had a number of works in print, but no true piano rags. According to an interview with Joe recorded in 1958, he was at Starks office one day purchasing some of Joplin's more recent works. Before leaving, he vocalized his wish to meet the master at some point, and the clerk pointed to a man with one leg wrapped up sitting across the room. "There he is." Lamb was enthralled, and after the accolades of admiration told Joplin that he had been writing ragtime too. So Scott arranged for Lamb to play some of these rags for him that evening (or an evening soon after) at a gathering. Among the pieces he played were his Old Home Rag and Dynamite, the latter of which Joplin provided a suggestion for improvement. Then Joe played his rag Sensation piano rag. By the time the white composer finished his performance the room full of Joplin's friends had gone quiet. Then, according to Joe, Joplin or one of his friends said, "That sounded like a good colored rag," which is exactly what Lamb had hoped to hear.

Then, according to Joe, Joplin or one of his friends said, "That sounded like a good colored rag," which is exactly what Lamb had hoped to hear.

Then, according to Joe, Joplin or one of his friends said, "That sounded like a good colored rag," which is exactly what Lamb had hoped to hear.

Then, according to Joe, Joplin or one of his friends said, "That sounded like a good colored rag," which is exactly what Lamb had hoped to hear.Joplin arranged to have Sensation published by Stark, with his name on it as arranger to help with sales, even though his input was likely nothing other than the moral boost. Stark paid the composer $25 with the promise of another $25 after the first thousand copies were sold. A second payment was indeed made a few weeks later, but nothing further for his first true sensation. Just the same, John Stark published pretty much anything Lamb sent him from that point on through 1919, even after the publisher retreated back to St Louis a couple of years later. His output of twelve piano rags with Stark easily rivaled Joplin's for quality and innovation, in spite of a lack of intensive formal schooling in harmony and theory. Lamb was an important link to Joplin and his era when Blesh and Janis interviewed him in the 1950s for They All Played Ragtime

While an article printed in the summer of 1907 suggest that Joplin was only planning to stay in New York for a few months, he had decided by early 1908 to settle there. Since he was known to have attended several of the Broadway shows of his peers, and also to have established some important musical and publishing relationships, Scott evidently felt that he would be better able to implement some of his plans in the difficult but supportive environment of Manhattan. Joplin also had good exposure there, and his name was found in the New York papers from time to time. Most of the articles mentioned his grand plan, the opera he had been working for some time.

His first publication of 1908 made a great deal of sense. A decade prior, stage entertainer Ben Harney, with the assistance of composer Theodore Northrup, had released the first Ragtime Instructor. Entrepreneur Axel Christensen, who had been humiliated with poor piano playing in his teens, struck back and became adept not only at playing ragtime but writing and teaching it as well. He opened a successful chain of ragtime, later jazz, teaching schools in Chicago that stretched far beyond. But in 1908 his efforts were still largely confined to Illinois. Others had picked up on this and also gone after the correspondence and teaching market, with primers on how to syncopate.

Others had picked up on this and also gone after the correspondence and teaching market, with primers on how to syncopate.

Others had picked up on this and also gone after the correspondence and teaching market, with primers on how to syncopate.

Others had picked up on this and also gone after the correspondence and teaching market, with primers on how to syncopate.Joplin countered these moves by creating his School of Ragtime, six piano exercises that touched on various points of syncopation. It was an effort to not just teach the consumer how to play syncopation, but to read and perform it properly. Unlike many previous efforts, Joplin's publication was aimed at interpreting piano rags in print, not so much in applying the ragtime style to other popular music forms. Perhaps more important than the six exercises are Joplin's written comments, which clearly provide his view of how ragtime should not only be performed, but written as well. In his introduction he lashes out at "publications masquerading under the name of ragtime," and touts "real ragtime of the higher class," which would obviously include his own and his closest peers. He further makes clear that poor or sloppy performance of ragtime could add to its already tenuous reputation, and included the requisite warning about playing it too fast. Joplin self-published the piece through Enterprise Music, a music jobber in Manhattan, who had also done business with Stark. He, in turn, carried the publication in his 23rd Street office.

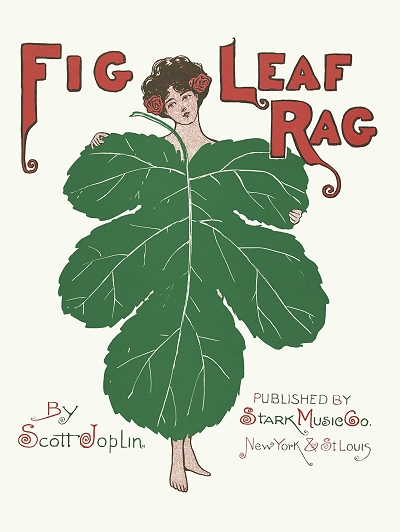

Fig Leaf Rag followed within a couple of months of School of Ragtime. Many historians have grouped it with Gladiolus Rag, Rose Leaf Rag and Nonpareil as one of the finest Joplin works of this period. There is an great deal of left-hand counterpoint found throughout, and even a couple of harmonic surprises in the A and B sections. The trio is a true masterpiece, albeit one of the most difficult Joplin trios to perform owing to the right-hand performing octave melody patterns throughout most of it. It is not as harmonically rich as Gladiolus, but the deep left-hand bass patterns give it a beautiful sonority of its own just the same. This would be the last Joplin rag published by Stark during the composer's lifetime.

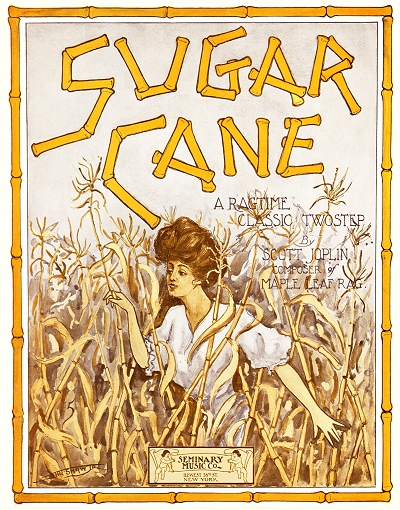

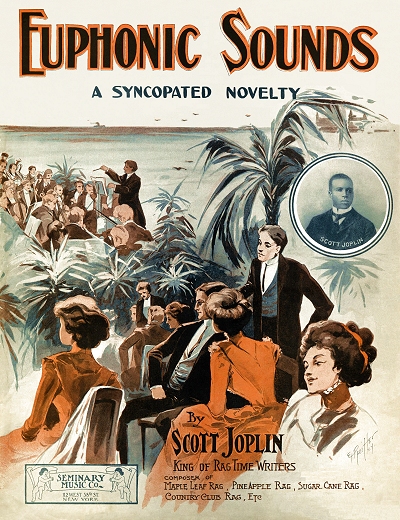

Next up was Sugar Cane Rag, the first of Joplin's pieces published by Seminary Music, which was run by composer Ted Snyder who would soon be in business with Irving Berlin and Henry Waterson. All this ties together in another story to be relayed. In 1908, however, Seminary was a small but effective firm that evidently offered Scott good terms.

All this ties together in another story to be relayed. In 1908, however, Seminary was a small but effective firm that evidently offered Scott good terms.

All this ties together in another story to be relayed. In 1908, however, Seminary was a small but effective firm that evidently offered Scott good terms.

All this ties together in another story to be relayed. In 1908, however, Seminary was a small but effective firm that evidently offered Scott good terms.Stark did not take well to Joplin handing Sugar Cane Rag to yet another publisher, and privately criticized the piece in the press, not without good reason either. "Joplin is now only living in the dream of Maple Leaf. No one will perhaps ever equal that ingenious piece nor his Sunflower or Cascades. His labored effort is but a rehash of these numbers which no self-respecting publisher would print." Sugar Cane Rag was clearly modeled on Maple Leaf Rag, closely enough that it could be considered a pale rewrite of the original, yet with some newer elements as well which give it an identity of its own. Stark had also noted in his personal writings that Joplin had been moving about from publisher to publisher trying to find the best deal, and learning that he could have got it from someone else. It is not clear if this was true, but it does reflect the experience of many black composers in New York even into the 1930s.

Just the same, Joplin stuck with Seminary for his next piece in the fall of 1908, one which was clear more original and fresh. Pine Apple Rag by nature was intended to be performed faster than some of the more recent Joplin rags. The B section used a repeated pattern that varied by chords only, but chews up a lot of the keyboard in the process. The trio contains some of the primary harmonic patterns, and predicts both blues and boogie or barrelhouse piano, both of which Scott had almost certainly been exposed to in New York. The left-hand plays a variation of what could easily be shifted into a boogie pattern in many spots, and the right-hand plays into a flatted seventh chord, which would be a staple of blues piano. Many pianists have since taken to playing this section with a swing and swagger befitting of blues players. The final section also contains a boogie bass, or at least one that easily becomes more of a boogie-woogie bass by doubling up on the left-hand notes in the familiar broken octave pattern of the genre.

Pine Apple Rag was dedicated to the "Five Musical Spillers," a traveling vaudeville group of which Sam Patterson was a member. Joplin also had a relationship with William Spiller, the leader. The group played a variety of instruments including brass and mallets. According to Berlin in King of Ragtime, they were already playing Maple Leaf Rag, and took on Pine Apple Rag as well, as later recounted by William's wife Isabele Spiller. Pine Apple Rag enjoyed new popularity along with The Entertainer in the 1970s thanks to the Universal Picture The Sting from 1973.

According to Berlin in King of Ragtime, they were already playing Maple Leaf Rag, and took on Pine Apple Rag as well, as later recounted by William's wife Isabele Spiller. Pine Apple Rag enjoyed new popularity along with The Entertainer in the 1970s thanks to the Universal Picture The Sting from 1973.

According to Berlin in King of Ragtime, they were already playing Maple Leaf Rag, and took on Pine Apple Rag as well, as later recounted by William's wife Isabele Spiller. Pine Apple Rag enjoyed new popularity along with The Entertainer in the 1970s thanks to the Universal Picture The Sting from 1973.

According to Berlin in King of Ragtime, they were already playing Maple Leaf Rag, and took on Pine Apple Rag as well, as later recounted by William's wife Isabele Spiller. Pine Apple Rag enjoyed new popularity along with The Entertainer in the 1970s thanks to the Universal Picture The Sting from 1973.While Joplin did seem to make some effort to reconnect with Stark, either to publish another rag or two, and perhaps to try and get backing for the opera, Stark had been embittered to some degree by the tough music business in New York City. There had been several sheet music price wars by the end of 1908, and even more were to come. Places like Woolworths were using cheap music as an incentive to get people in the doors, and they were selling music at or below cost, something which hurt other merchants, and ultimately the publishers and composers.

According to Lamb, Stark made it clear that he would not be paying any more royalties on new pieces. Between that and his refusal to consider Treemonisha, the relationship between Joplin and his most avid and able supporter was over. Lamb recounted that he and Joplin had co-composed a rag around 1909, writing two sections each, with Joe taking on the trio and the closing. Stark stated he would consider it only if Joplin's name was removed from the work. Since Lamb would not even consider this, the rag was taken back, and is now presumed lost to history. Stark's business was already hard hit by financial woes, and by 1910, with his wife ailing, John Stark would close his New York office and retreat to St. Louis where things made more sense. Sadly, his wife would die very soon after their return.

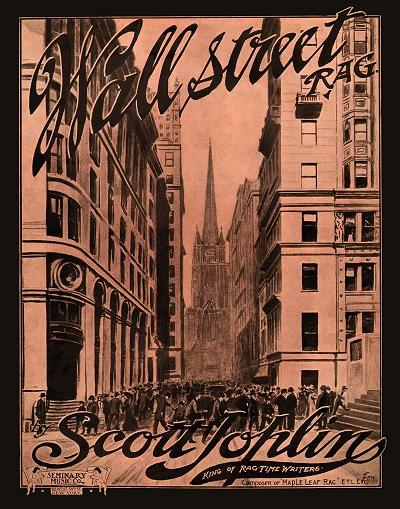

Finding the treatment of both himself and his rags by Seminary to be favorable, Joplin submitted Wall Street Rag to Snyder in early 1909. Other than The Ragtime Dance, which was really music with a set of stage instructions, this was his only descriptive piece in addition to The Great Crush Collision more than a decade earlier. E.T. Paull had been doing a booming business, in spite of having only published an average of two pieces per year since 1903, with his descriptive marches. Given his presence among publishers and composers in New York and in various organizations, plus frequent mentions in the trade, it is more than likely that Joplin was quite aware of Paull. Whether or not the work of the New York march king influenced Wall Street Rag is a matter of conjecture, but the author, who has written a full book biography on Paull, is inclined to believe that this is a probability.

but the author, who has written a full book biography on Paull, is inclined to believe that this is a probability.

but the author, who has written a full book biography on Paull, is inclined to believe that this is a probability.

but the author, who has written a full book biography on Paull, is inclined to believe that this is a probability.Paull's works used music to either describe the emotion behind a certain moment, or in some cases the tenor of the event each section or passage was meant to convey. In this regard, Joplin applied a similar description to each of his sections, and like with many Paull marches, did not return to the A section, further suggesting Paull's influence. Part of the logic of this is that in order to move a story forward musically, a backwards move, such as the repeat of a section, is counter-intuitive. The descriptions for each section are as follows:

A: Panic in Wall Street, Brokers feeling melancholy.

B: Good times coming.

C: Good times have come.

D: Listening to the strains of genuine negro ragtime, brokers forget their cares.

The significance of this was that Joplin was attempting programmatic music, and it may have been related to ongoing work with Treemonisha as well. The opening section is indeed quite melancholy with minimal left-hand movement in the opening measures, focusing on the tonic and the flatted sixth. It is rhythmically reminiscent of Heliotrope Bouquet. While the second and third descriptions are a sort of cheat that play on each other, they are more traditional in their harmonic movement. The trio moves the melody above and below a persistent harmony, all in the right-hand. The final section does, in some ways, emulate the plucking of a banjo. It is unlikely this rag would have been written in St. Louis, so Joplin was now very much a New Yorker.

The habanera rhythm had been a popular staple of ragtime composers for nearly fifteen years. Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton would become one of the most frequent users of the African-based rhythm, which in his hands would become known as the "Spanish tinge." Black composers Ford Dabney and Will Tyers would also make use of it, as would Artie Matthews in his Pastime Rags. Often misinterpreted as a tango rhythm, which has some not-so-subtle differences, many so-called tango were released starting just prior to 1910 which were based on habanera patterns. If there was no other prescient exposure to this rhythm in pop music, most musicians had heard it from the opera Carmen and its famous Habanera dance.

Black composers Ford Dabney and Will Tyers would also make use of it, as would Artie Matthews in his Pastime Rags. Often misinterpreted as a tango rhythm, which has some not-so-subtle differences, many so-called tango were released starting just prior to 1910 which were based on habanera patterns. If there was no other prescient exposure to this rhythm in pop music, most musicians had heard it from the opera Carmen and its famous Habanera dance.

Black composers Ford Dabney and Will Tyers would also make use of it, as would Artie Matthews in his Pastime Rags. Often misinterpreted as a tango rhythm, which has some not-so-subtle differences, many so-called tango were released starting just prior to 1910 which were based on habanera patterns. If there was no other prescient exposure to this rhythm in pop music, most musicians had heard it from the opera Carmen and its famous Habanera dance.

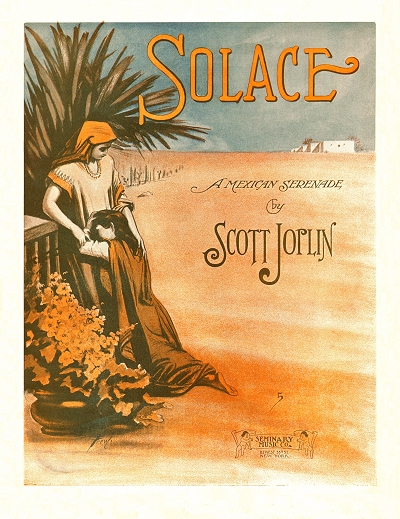

Black composers Ford Dabney and Will Tyers would also make use of it, as would Artie Matthews in his Pastime Rags. Often misinterpreted as a tango rhythm, which has some not-so-subtle differences, many so-called tango were released starting just prior to 1910 which were based on habanera patterns. If there was no other prescient exposure to this rhythm in pop music, most musicians had heard it from the opera Carmen and its famous Habanera dance.Joplin, while not ahead of the curve, did treat the rhythm with more respect when he composed Solace. It was subtitled "A Mexican Serenade," which was somewhat more proper than calling it a tango, and it was certainly not a rag either. If not for its syncopation, Solace might have been called an intermezzo, but was saved from this fate by syncopation throughout. This lyrical piece, of which the trio and D sections were made famous by the soundtrack for The Sting in 1973, also called on some of the harmonic progressions of Mexican music of that time. It is not unlikely that Joplin would have had exposure to this during his travels in Texas, and even perhaps in St. Louis when Mexican musicians would come through town on a U.S. tour. Published by Seminary, it also stands out among Joplin works for the beautiful four-color cover by Irish artist John Frew, who had also contributed artwork for Wall Street Rag and his next Seminary publication, Pleasant Moments.

Having not written a waltz for some years, Joplin came up with a beautiful syncopated three step with Pleasant Moments. In some ways it was closer to rag form than Bethena. The C section was at once both strong and delicate, and invited improvisation on the repeat. He would revisit this waltz in a few years. In the meantime, he kept Seminary Music supplied with rags and they consistently issued them. Country Club, copyrighted the same day as Pleasant Moments, is the simplest of all Joplin rags, and certainly the most delicate. The structure of it does not invite a speedy interpretation.

Euphonic Sounds might be considered a revolutionary ragtime experiment of some kind. Instead of titling it as a rag, he called it a "syncopated two-step." While the piece contains a great deal of right-hand syncopation, the differences from his previous works are in the treatment of the left-hand and the harmonic content. There is a nearly complete absence of the traditional duple or oom-pah ragtime left-hand in Euphonic Sounds, replaced by intricate arpeggios and moving patterns, contrary motion and repeated chords. The B section travels into unfamiliar territory for virtually all piano rags up to that time, working with bold changes and a difficult decrescendo on repeated right hand octaves. The trio is also harmonically challenging, but with a more static left-hand riff.

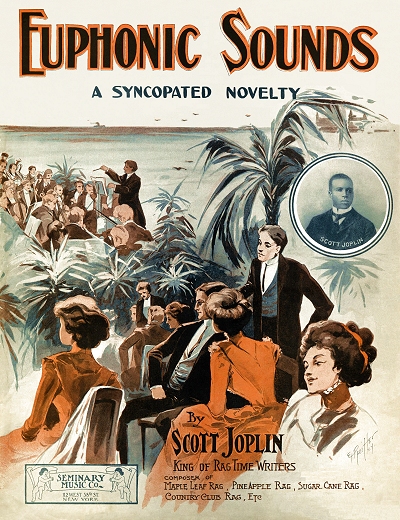

Scott's final submission of 1909 for Seminary Music was Paragon Rag. More traditional by far in structure, it had yet another interesting feature that showed Joplin's knowledge of performance. In the measures three and four and corresponding measures of the B section, the right-hand phrase from the previous measures settles into a held chord while a pattern is played above it in the same hand. The only way to properly execute this was on a piano with a sostenuto pedal, mostly a staple of grand pianos but rarely found on all but the most expensive of uprights. This center pedal, when depressed, holds the dampers for only the notes currently held down, and sustains only those notes while others are played. This technique would become a standard of novelty and stride pianists, particularly for the left-hand, but was very unusual in piano ragtime. Composer Clarence Woods of Missouri would use the same type of notation in his iconic Sleepy Hollow Rag in 1918. The trio of Paragon Rag bears some similarity in the left-hand to Euphonic Sounds, and the D section a bit more adventurous in phrasing than most of his 1908 works had been. The piece was dedicated to the Colored Vaudeville Benevolent Association (C.V.B.A.), of which William Spillman was a member. He had recently become a member of the association and would remain active in it over the next few years.

Now assimilated into the musical world of New York, Joplin became better known to publishers and musicians alike, and reported befriended many of the black composers in town while rubbing elbows with many others. He found favorable mention in the New York papers and the music trade papers. However, the end of the decade proved to also be end of his most productive and creative period in terms of piano rags. Having talked about his opera project for nearly three years, in 1910 it would become his primary focus. Sadly, his favorite musical child would also lead, in part, to his tragic downfall, and decades later, a posthumous triumph.

Treemonisha and Troublesome Times